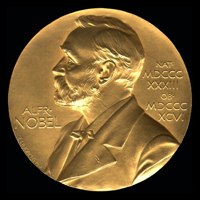

The Nobel Prize Is Really Annoying

One of the chapters in Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman is titled “Alfred Nobel’s Other Mistake.” The first being dynamite, of course, and the second being the Nobel Prize. When I first read it I was a little exasperated by Feynman’s kvetchy tone — sure, there must be a lot of nonsense associated with being named a Nobel Laureate, but it’s nevertheless a great honor, and more importantly the Prizes do a great service for science by highlighting truly good work.

One of the chapters in Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman is titled “Alfred Nobel’s Other Mistake.” The first being dynamite, of course, and the second being the Nobel Prize. When I first read it I was a little exasperated by Feynman’s kvetchy tone — sure, there must be a lot of nonsense associated with being named a Nobel Laureate, but it’s nevertheless a great honor, and more importantly the Prizes do a great service for science by highlighting truly good work.

These days, as I grow in wisdom and kvetchiness myself, I’m coming around to Feynman’s point of view. I still believe that on balance the Prizes are a very good thing, and generally they honor some of the very best work in physics. (Some of my best friends are winners!) But having written a book about the Higgs boson discovery, which is on everybody’s lips as a natural candidate (though not the only one!), all of the most annoying aspects of the process are immediately apparent.

The most annoying of all the annoying aspects is, of course, the rule in physics (and the other non-peace prizes, I think) that the prize can go to at most three people. This is utterly artificial, and completely at odds with the way science is actually done these days. In my book I spread credit for the Higgs mechanism among no fewer than seven people: Philip Anderson, Francois Englert, Robert Brout (who is now deceased), Peter Higgs, Gerald Guralnik, Carl Hagen, and Tom Kibble. In a sensible world they would share the credit, but in our world we have endless pointless debates (the betting money right now seems to be pointing toward Englert and Higgs, but who knows). As far as I can tell, the “no more than three winners” rule isn’t actually written down in Nobel’s will, it’s more of a tradition that has grown up over the years. It’s kind of like the government shutdown: we made up some rules, and are now suffering because of them.

The folks who should really be annoyed are, of course, the experimentalists. There’s a real chance that no Nobel will ever be given out for the Higgs discovery, since it was carried out by very large collaborations. If that turns out to be the case, I think it will be the best possible evidence that the system is broken. I definitely appreciate that you don’t want to water down the honor associated with the prizes by handing them out to too many people (the ranks of “Nobel Laureates” would in some sense swell by the thousands if the prize were given to the ATLAS and CMS collaborations, as they should be), but it’s more important to get things right than to stick to some bureaucratic rule.

The worst thing about the prizes is that people become obsessed with them — both the scientists who want to win, and the media who write about the winners. What really matters, or should matter, is finding something new and fundamental about how nature works, either through a theoretical idea or an experimental discovery. Prizes are just the recognition thereof, not the actual point of the exercise.

Of course, none of the theorists who proposed the Higgs mechanism nor the experimentalists who found the boson actually had “win the Nobel Prize” as a primary motivation. They wanted to do good science. But once the good science is done, it’s nice to be recognized for it. And if any subset of the above-mentioned folks are awarded the prize this year or next, it will be absolutely well-deserved — it’s epochal, history-making stuff we’re talking about here. The griping from the non-winners will be immediate and perfectly understandable, but we should endeavor to honor what was actually accomplished, not just who gets the gold medals.