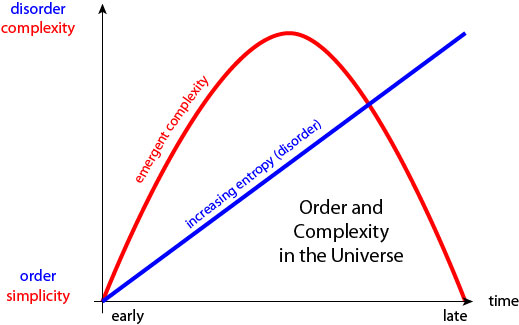

Our observable universe started out in a highly non-generic state, one of very low entropy, and disorderliness has been growing ever since. How, then, can we account for the appearance of complex systems such as organisms and biospheres? The answer is that very low-entropy states typically appear simple, and high-entropy states also appear simple, and complexity can emerge along the road in between. Today's podcast is more of a discussion than an interview, in which behavioral neuroscientist Kate Jeffery and I discuss how complexity emerges through cosmological and biological evolution. As someone on the biological side of things, Kate is especially interested in how complexity can build up and then catastrophically disappear, as in mass extinction events.

There were some audio-quality issues with the remote recording of this episode, but loyal listeners David Gennaro and Ben Cordell were able to help repair it. I think it sounds pretty good!

Support Mindscape on Patreon.

Kate Jeffery received her Ph.D. in behavioural neuroscience from the University of Edinburgh. She is currently a professor in the Department of Behavioural Neuroscience at University College, London. She is the founder and Director of the Institute of Behavioural Neuroscience at UCL.

0:00:00 Sean Carroll: Hello everyone and welcome to the Mindscape podcast. I'm your host, Sean Carroll. We have yet another experimental kind of podcast today. Our guest is Kate Jeffrey, who is literally an experimentalist, an experimental neuroscientist at University College London, where she studies the cognitive map within the brain. How we find where we are in the universe, and how that triggers certain neurons in our brains. But we're not gonna be talking about neuroscience, for the most part. Kate and I were both participants in a workshop in Costa Rica, a covley workshop on space, time, and the brain. On this general idea of relating space and time to how they're represented in brains. I gave a talk while I was there on complexity and its relationship to entropy, and Kate, hearing the talk, responded to it in her own talk, talking about the evolution of complexity in a biological and environmental context.

0:00:57 SC: Where things are much more subtle and nuanced and a lot of details, that as a physicist, I could gloss over. So together we thought that it would be fun, rather than just me interviewing her about her stuff, to talk about this area of the relationship between entropy and complexity, how complex structures come to be over time, whether it's cosmologically, here on Earth, or even within a social domain. And then how complexity goes away. There can be catastrophes, right? There are extinction events. There's the ultimate equilibration of the universe. So this is, more than any other podcast I've ever had, I think I am doing just as much of the talking as my official guest. It's possible that I'm doing more of the talking than Kate did. But anyway, we're both sort of trying to learn things. This is neither one of us laying down the law from on high. It's a true interdisciplinary exploration, and I think you're gonna find it's a lot of fun. So, let's go.

[music]

0:02:11 SC: Kate Jeffrey, welcome to the Mindscape podcast.

0:02:13 Kate Jeffrey: Thank you.

0:02:14 SC: So this is an unusual, but fun episode I think, in the sense that we're gonna try to make it a two-way conversation, right? Some podcasters just make every one of their conversations a two-way conversation. I do try to let the guest do most of the talking, but we're gonna be a little bit more balanced here. To maybe explain why that's the case, why don't you give us some of your background, what you do for a living in your respectable part of your day job.

0:02:42 KJ: So I'm not a physicist at all, so I have to start with an immediate disclaimer here. I'm a neuroscientist, and I'm interested in how the brain makes an internal representation of the world, to how it creates knowledge structures. And I do that by implanting electrodes into the brains of rats and mice, and listening to the signals and then trying to correlate what we can pick up with what the animal, with its sensory inputs, its behavior. And we're really trying to understand how it comprehends space and forms memories of its experiences and all that kind of thing. So that sort of led me to thinking about space and time, and what that actually means. And I came up with some bigger questions, and that's how I kind of started straying into your domain, to some extent.

0:03:38 SC: Right, well we were at a conference together, a covley workshop in Costa Rica on space, time, and the brain. So those are three big topics, obviously. And I gave a talk where I gave part of my usual spiel about entropy and complexity, and I can rehearse that here. But then you gave a talk that sort of built on that in some way. Were you already thinking along these lines? You must've been, you seemed pretty prepared.

0:04:00 KJ: Yeah, so I had come along to that meeting prepared to talk about how the brain makes a map of three-dimensional space. But my talk was on the last day, and by the time we had got to that point, and the physicists and the neuroscientists had exchanged a few conversations, I felt that I had less to contribute that was gonna be useful about my research, and more to contribute about some other things that I've been thinking a lot about. So I had never actually formalized those things before, so I had to kind of sit down and construct from scratch sort of an assemblage of my ideas. But what I had been thinking about for the last few months is how the nervous system has really come to be in the course of the evolution of the universe, and the evolution of life. And how it's managed to navigate the various bumps in the road along the way.

0:05:09 KJ: So there have been a number of major extinctions, for example, in the evolution of life. And of course we're facing another one at the moment, which has been occupying my thoughts a lot. So I've just been thinking about the fact that life seems to be inherently unstable, and yet we've seen more and more of it accumulate as the universe has gone on. And I just got curious about the dynamics of that. Why does that happen? So it was fantastic to be able to talk to you physics guys who all have a thermodynamic kind of understanding. And when you talked about complexity and entropy and all of that, I just had so many questions. So I thought, "Well, I'm gonna lay out some of my questions, and then we can talk."

0:05:49 SC: Yeah, and here we are. You're doing it. This is sort of the culmination of that.

0:06:31 SC: Cool. So, how should we do this? You want me to start with my... Like I said, my conventional spiel about entropy and complexity, and then we can build on that? 'Cause I think that your take on it is in many ways a lot more nuanced. I'm just doing the simplest physics thing, where we try to get everything is a spherical [0:06:50] ____ and everything is very simple and as someone who cares about life and biosphere and things like that. You are very correctly saying it's a bit more complicated than that, when we get to the real world.

0:07:00 KJ: Yeah. So yeah, I think you should start definitely.

0:07:03 SC: Okay. So this is something where I became interested in it, because I became interested in entropy. Entropy, for those out there who somehow have escaped me talking about this, is a way of talking about how disorderly or how disorganized things are, and more particularly if you have a set of tiny little constituents, atoms or molecules or cells or whatever and there are different ways to arrange them microscopically and you can see certain features of those macroscopic arrangements. So, you look at, my favorite example is a cup of coffee with cream being mixed into it. You see where the cream is, you see where the coffee is, but you don't see where the individual molecules are. So, Ludwig Boltzmann in the '1870s said, "Entropy is basically a way of counting how many ways there are to arrange the microscopic constituents to give you that macroscopic look."

0:07:55 SC: So in other words, we course-grain the description in terms of what we can see about it macroscopically, and then we just count the number of microscopic states that would contribute to that way being. And there's a rule, the second law thermodynamics, it says that typically the entropy increases because very naturally, if you start in a configuration where there's only a small number of arrangements that look that way, just by natural evolution, without any direction, you will move toward a situation where you're in a higher entropy state 'cause there are more ways to be high entropy, than to be low entropy. That's a very quick second law of thermodynamics, intro, but that makes sense, right?

0:08:35 KJ: Yeah.

0:08:36 SC: Do you use the second law of thermodynamics a lot as a working psychologist biologist?

0:08:40 KJ: Not me personally, more theoretical neuro-scientists think about it in terms of free energy and high inflation theory and that type of thing. I just tend to encounter it when I messed things up in an experiment, it all comes out wrong.

0:08:57 SC: Entropy is part of our daily lives. That's certainly true.

0:09:01 KJ: So, just to ask you a bit more about this notion because I understand how it works for a box of gas molecules, let's say. But I start to run into difficulties of understanding when I think about, for example, the entropy in a molecule of DNA. So, it seems to me that the number of microscopic states that correspond to that macroscopic state, there's more than... There's more than one set of numbers, if you like. So one of them is the number of microscopic states that would just lead you to a coiled molecule, and one of them is the number of microscopic states that would lead you to the genome for cyanobacterium, let's say.

0:09:52 KJ: So, microscopically, they look exactly the same, it's a spiral molecule, but the functioning of that molecule in the bigger picture is completely different. So I struggle with saying that the entropy of those two molecules is the same, but my understanding is that a physicist would say, "Well, it is."

0:10:13 SC: Well, I think that a careful physicist would say, it depends. In the sense that if you put your finger on one of the long standing controversial aspects about the Boltzmannian statistical mechanical way of talking about entropy, which is that it seems to involve some human choices in the definition of things. I tried to make it sound pretty objective by saying the macroscopic features that you can observe are how you course-grain microscopic states into macroscopic ones, but someone could say, "Well, who is doing the observing? Does a better observer see a different entropy than a worse one?" To a large extent in practice, that's not a big worry because the laws of physics make certain features microscopically observable to us and not others.

0:11:04 SC: So when we see the cream in the coffee for example, even if you built a robot, or even if you met an alien or whatever, none of them is gonna be able to see the individual molecules and their positions and momenta, they're basically gonna see the same things that a human being sees. So, there is something robust about nature that suggests certain ways of course graining into macro states. But when you get to the edge cases where there's not a lot of moving parts, we're used to having Avogadro's number of molecules and you're used to having a much smaller number than that. So in a DNA molecule, versus some other sort of polymer of some sort, yeah, what exactly you count as the microscopic constituents and how you course grain them into macro-states can matter, can be different. And it might depend on functionality, I think, which is what you're getting at.

0:12:00 SC: Two molecules that might look the same physically from just sort of if your course graining is just, how long is it? How stretchy is it? How bendy is it? Two molecules might look the same but if you're asking, what is its function in the cell, those same two molecules might look very different. I think that my answer is use whatever one you want, just be consistent once you start using it. So I don't think that the right physics answer is to say, No, you have to ignore the detailed differences between DNA and some other long molecule. I think that it just depends on what context you're working in and I think also that's okay, I don't think that's a flaw I just think it's something to recognize.

0:12:46 KJ: But are you saying that entropy is a subjective thing then, that it's context-dependent?

0:12:53 SC: It is subjective in a sense, but it's in the following sense, the same thing is true I would say about any emergent phenomenon. Whenever we have a microscopic description, which is highly accurate, perhaps perfectly precise and there's a macroscopic description in different terms, which is only a good approximation, it's always the case where we don't have to use that macroscopic approximation. If we were Laplace's demon, if we knew the location of every molecule Freeman coffee in the cup and could do the calculations in our head, we wouldn't need to course grain, at all, but nevertheless there is something real and useful about the course graining. There's certain ways of course graining that would make no sense. We course grain the coffee by saying in every little region of space we'll count the number of coffee molecules and cream molecules or whatever. We don't say we'll average the number of molecules over here, then a number of molecules at a completely different place for some arbitrary crazy reason.

0:13:54 SC: And the reason why is because course graining in that way, would give a description that has no simple dynamics, it's not robust. The nice thing about emergence is you throw away an enormous amount of information, the locations and velocities of every individual molecule, but what you keep is still somehow representing a true pattern in the dynamics.

0:14:19 KJ: Yeah, I kind of get that, but I still feel there's a fundamental issue. So if you take a stretch of DNA that is meaningful. So, it's genes for some organism. Then as time goes by, and mutations occur. And the DNA degrades, the molecule will have the same macroscopic properties, but it will be degraded within the bigger picture. So, in some senses, the information content which I kind of feel is somehow associated with entropy, the information content has gone down, even though the macroscopic qualities at that moment haven't changed. But where the macroscopic properties have changed is when you look at what happens to that molecule in time because after the mutation, it's gonna build a very degraded funny-looking organism instead of a normal looking one.

0:15:23 KJ: So, I'm struggling really with this notion of what is meant by macroscopic properties. Are they just slices in the here now or do you need... Consider the entire history of that system over time as well as within the space?

0:15:43 SC: Well, certainly the usual way of doing it, the history over time wouldn't matter. If it does matter then your physical description is enormously more complicated, it's not that it's impossible, but we very much like in physics to think in Markovian terms. Markovian just in the simple sense that what happens at one moment depends on what happened in the immediate previous moment, but not the entire history of the past. And likewise, the future is predictable from right now, not from information in the past. But what kind of prediction you're making is certainly relevant when you decide what is the information that you use that you take into account when you make your macro states.

0:16:27 SC: So, if you care about the function of that molecule within the cell, then I certainly think that there are features of the cell that would go into your course... Features of the molecule that would go into your course graining like a slightly degraded DNA molecule that didn't do its biological function. It would be completely legit to count as a different macro state than one that looked pretty much physically the same but did its function perfectly well.

0:16:54 KJ: But then you have taken time into account because function is a thing that happens in time.

0:17:00 SC: Well, I would say that what I'm taking into account is counterfactual statements, like would the molecule act differently even right now if different things were happening to it? I think that's okay to take into account, but I don't need to actually see into the future to see what will happen to this actual example of the molecule.

0:17:21 KJ: But you wouldn't be able to distinguish a degraded DNA from a well-formed DNA molecule in that sense until you had seen what happened to it in the future or knew the gene sequence. Something like that.

0:17:36 SC: Yeah, you wouldn't be able to tell just by looking at it, I guess, is what you're saying, right? By using the immediately macroscopic available information to you, you would not be able to distinguish between them.

0:17:46 KJ: Yeah and indeed it has no meaning until you consider its future.

0:17:53 SC: Yeah, I think this is a subtle edge case where you have... There's a whole discussion. There are people who know a lot more about this than I do, but there's a whole discussion about hidden states within some macro states. So ordinarily in statistical mechanics, your hope is that all of the micro-states within a macro state not only look the same, but for the most part they will act the same. Now you know that that's not exactly true. Within some macro state of a glass of water, there is some individual micro-states where suddenly the water will heat up, except an ice cube will form in the water, that's extremely, extremely unlikely and it's a very, very tiny number of micro-states. But they exist and you would never know just by looking at the glass of water. But we get around that by saying, well, there's just so few of those we can ignore them.

0:18:44 SC: And again, when you get down to a small number of moving parts, you might not be able to ignore that. So I think that a lot of it just comes down to the fact that you might not be able to reliably use some of these statistical mechanical ideas in regimes where Cellular Biology or nano-scale physics really matter.

0:19:07 KJ: That seems like a big statement. Because the Second Law of Thermodynamics is that not supposed to govern the unfolding of the universe including living things?

0:19:18 SC: Well, yes, but the universe has a lot of moving parts in it. And look, if you have three moving parts, there's no such thing as the Second Law of Thermodynamics, right? It's just a waste. If you have 100, then there's a reasonable approximation to it, and if you have 10 to the 10, then it's really, really, really good. So we gotta accept that. Fluctuations and unlikely events are hugely important at the level of cellular biology. They're completely irrelevant at the level of what goes on in your internal combustion engine.

0:19:53 KJ: Yeah, so I guess the thing that's been bothering me about entropy has been this apparent subjectivity.

0:20:01 SC: Yeah.

0:20:02 KJ: The other thing I've struggled with is the way in which it requires space to be meaningful because all of the descriptions of entropy at the sort of thermodynamic level involve space and involve things being in one part of space or the other is that a fair statement?

0:20:27 SC: Well, it's a fair statement in physics generally that space is really important in the sense that space is... And I'm thinking I'm talking slowly because as a physicist, I'm trying to answer questions about why is their space in the first place, which you're not worried about heavily and we're not worried about for this conversation, but roughly speaking, space is the arena in which interactions between physical systems look local, right?

0:20:55 SC: Two objects will interact with each other when they are at the same or almost the same location in space in a way that they won't interact with each other if they have the same velocity, but are in very different locations in space, right? So space is very, very special for exactly that reason. And I think that that should be true even for biology, but you sound like maybe you're worried about it.

0:21:15 KJ: Well, I am a little, I don't know if worried is the right word, but in thinking about entropy at the thermodynamic level it seems to be to do with probability of... For example, a particle being in a particular part of the space. That has gotten woven in with my thinking about evolution and why evolution has proceeded the way it has, and then why life is slowly increased in complexity the way it has? And it seems to be that space is a very fundamental part of that process and what's happening as life evolves is the life forms are discovering new ways of extending the operation of their activities in bigger spaces or ever bigger times and that opens up new possibilities for entropy to flow.

0:22:10 SC: Yeah, no, I think that's exactly right. So maybe I can sort of build on the little spiel I gave about the Second Law and talk about complexity, a little bit 'cause again, I'm thinking about it at the most very basic physicist level, but we wanna get a little bit more nuanced during our conversation here. So if you believe that the history of our universe, the last 14 billion years has been a history of increasing entropy, of increasing disorderliness and randomness then it's perfectly okay to wonder how complicated organized structures like you and me or the biosphere, or whatever came into existence.

0:22:46 SC: There's a sort of bad creationist argument that says it couldn't have happened because the biosphere is very organized and the second law says things just become more disorganized. That's obviously wrong, because the second law only says that entropy increases in closed systems, and the earth and its biosphere are nowhere near a closed system. We're getting wonderfully low entropy energy from the sun, we are increasing the entropy of that energy and we're sending it back to the universe with much higher entropy. So the net effect of the earth on the entropy of the universe is certainly to increase it in complete accord with the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

0:23:27 SC: But that just says it's okay. It's allowed that complex structures such as life appeared on earth it doesn't explain why it should happen. So, with Scott Aronson and some other folks, some students, and postdocs. Lauren Willette and Brent Werness, we study this question, and we propose the following thing, which apparently is not completely new, but well, it's a little bit new but it's related to older ideas. As entropy increases in a closed system if you think about it carefully when entropy is really, really low things are organized, things are... Even though that's what it means for entropy to be low but not only are they organized, they're simple. There's not that many ways to be really, really low entropy.

0:24:12 SC: So if all the cream is on the top of the cup and all the coffee is on the bottom, that's low entropy and simple. Whereas, when things are high entropy, when all the cream and coffee are mixed into each other things are simple again, right? Everything is mixed together. That's very, very simple. It's in between that complex structures are allowed to exist and then you can ask the question, "Is it actually the case that in the course of physical evolution complex, structures do come to exist?" So do the cream and coffee simply smoothly blend into each other and everything is simple all along the way or is it more like you're stirring with a spoon, and you get some complicated fractal patterns in it?

0:24:52 SC: And so we did some simple simulations and we showed that you can get either one you can get either kind of behavior and in cases where you wanted to get complex structures forming that was allowed as long as there were correlations in how the cream and coffee mixed into each other. So our hypothesis is, number one, that as entropy goes up complexity starts low grows, and then fades away again.

0:25:18 SC: And number two, there are situations in which that will happen and situations in which it won't, and at least one of the ingredients you need for it to happen are correlations in the evolutions. It can't just be that one thing interacts with a thing right next to it. There has to be some rigidity or some long-range forces that are pushing things together in concert so that structure forms on all sorts of different scales. So the lesson that we take from that which is not nearly justified by the work we did, but I think it's the extrapolation of it is that the formation of complex structures like the biosphere and individual organisms here on earth is not just despite the fact that entropy's increasing, it's because of entropy increasing. If it weren't for entropy increasing, we'd be in equilibrium, where you have high entropy already and there would be no living structures. So we, our existence as organized low entropy creatures is actually part of the general tendency of things in the universe to increase in entropy overall.

0:26:24 KJ: But what is driving the temporal unfolding of the increase in complexity followed by the decrease in complexity? Like what is the thing that's shaping that evolution of complexity?

0:26:40 SC: Right. Well, so, I think, again, there's two things, there's a simple thing that it's allowed. Like, really it's not allowed to be complex when entropy is super, super low and it's not allowed to be complex when entropy is super, super high. The only place that complexity could exist is in between. And then the only question is, does it, as a matter of fact, come into existence. And that's the complicated one. So, we gave this really, really simple, very kind of village idiot kind of answer which is that you need some long-range correlations or long-range structures. So, I think the correct thing to do like the next step, is for me to hand over to you [laughter] and say in the real world, how did it happen and what lessons does that give us for the larger physics questions of how might it happen in principle?

0:27:31 KJ: Yeah, so when I listened to you talk about this in Costa Rica, I had an aha moment when you talked about these correlations in space, across space and time because that suddenly seemed to me to explain why life becomes more complex. Because what happens as life has evolved is that with each step and evolution, something has happened that has suddenly enabled organisms to become much more correlated over bigger areas and we have known for a long time that evolution has taken place in these kind of step transitions. So for example, for a billion years or so there were just cyanobacteria and everything was very boring.

0:28:28 SC: Yep.

0:28:30 KJ: And then suddenly things happened, for example, suddenly 500 million years ago, multi-cellular life evolved. Suddenly organisms were able to do a lot more than they could because once clusters of cells were able to interact and were able to correlate their activity, they were able to do tricks. For example, they could divide up tasks between them, one end could be for gathering food and one end could be for excreting food, all of that kind of stuff. And there are a number of such transitions. The evolution of the nervous system is another one. Suddenly an organism could convey a message from one side of the cluster of cells to the other side, and so they could coordinate their activities, they could do things like contract muscles and move, and then when they became able to move, they could move out of one patch of food into a new patch of food, and just... Just open up all sorts of amazing things. And there have been a number of these. And with each step, suddenly organisms have managed to extend their reach and become much more complex. And humans, I think are a fantastic example of that, and we're now extending our reach out across space and out across time and into higher dimensions, and amazing stuff that we're doing.

0:30:00 SC: Yeah, and I think that... So I think that one of the issues here, one of the features here is that complexity can build upon itself. This is certainly the lesson both of the origin of life and of the origin of multi-cellularity that there's only so many things that can happen if there's no life around or if all the life is unicellular and the space of possibilities becomes enormously bigger as this phase transition happens. So physicists think about these transitions as phase transitions where the sort of one type of thing happening and then suddenly a little bit of something new comes on the scene and can take over because it's so much more advantageous. And, again, the biology needs to be a little bit richer and more nuanced here than the physics does because... So, okay, fine, there can be a phase transition and you can explore different parts of the possibility space but how exactly does that happen? And yeah, physicists are allowed to think of things happening in arbitrary numbers of dimensions or arbitrary amounts of time, but you wanna think of things happening in the real world, and it matters, chemistry matters as well as biology. What molecules can you build and how can they interact with each other?

0:31:17 SC: And it's certainly, I think... It's uncontroversial to say that the origin of multi-cellularity opened up a huge space, and in fact, 500 million years later, we're not anywhere near done exploring it. Things are still changing very rapidly. The invention of technology has opened up a whole new set of dimensions of space, of possibility space if not space, space. But do you have a feeling for sort of what general lessons we can learn from these transitions or the existence of them?

0:31:46 KJ: Well, one of the things that's quite notable if you look over the evolution of complex life is that there have been periods of time where there's been a sudden decrease in complexity as well. So, there have been several major extinctions where suddenly things have gone backwards in very large steps, and indeed life has nearly being obliterated several times. So for example, when organisms discovered how to photosynthesize and suddenly reach out in space to grab the energy of the sun, if you like. They produced as a by-product of that activity, oxygen and the oxygen levels in the atmosphere rose very high, and of course oxygen is very toxic, and there was what they called the great oxygenation catastrophe, a big sudden fall in bio-diversity. And there have been other things.

0:32:50 KJ: So for example, when organisms discovered how to move, they discovered how to burrow through the substrate that they were living in in the bottom of the ocean and that allowed mixing of the water in the ocean with the substrate underneath and completely changed the chemistry. And again, there was a big extinction and a lot of life forms disappeared. They didn't all and, of course, the ones that were left then gave rise to what came after. And in fact, there was a huge explosion of life after that. We had these several extinctions. And life has managed to recover, but there is this feeling when you look at it that it might not have done, that it might have been the case that the extinction had been total. And I can't see anything in thermodynamics that rules out that possibility.

0:33:46 KJ: And of course, the situation that we're in right now, where we have extended our complex reach over space and time further than any life forms ever have before, that also opens up more possibilities for extinction than life has ever had before. I think that's a necessity.

0:34:03 SC: Yeah, no, this is absolutely... And I think that there is no thermodynamic guarantee that we couldn't extinguish all of life, but let's for the non-biologist out there, including myself, let's dig into this statement that it was almost extinguished. Is that in terms of a number of species or the number of organisms? I would think that there's still gonna be some unicellular organisms that would tough it out even in these big events. But maybe I'm wrong.

0:34:31 KJ: Well, the ones that have happened up to now have indeed left a lot of life still going, both in terms of number of species and in terms of numbers of genomes, if you like, individuals, but it's not necessarily the case. For example, if we managed to turn the Earth into Venus or cover it in radio activity, then perhaps we can obliterate all life. So we don't know that life, which when you look at it, life seems to be very dynamic and inherently unstable and rapidly changes into wonderful complexity but it does feel like it could also rapidly run into a wall. So something I've been thinking about a lot is, are we about to do that? And if we are, can we stop it?

0:35:20 SC: So I think that thermodynamics gives us no solace here. I do think that this is an important difference between the very simple example that we looked at with cream and coffee where the complexity just smoothly went up and then smoothly went down, roughly speaking, because it was kind of a... It was kind of featureless. There's only two things, there was cream molecules, as it were, in our simulation and coffee molecules. There was not a lot of room for different kinds of things, but I think what you're getting at is that in the specific case of life, there's sort of mechanisms for this complexity that are very specific, that there's certain biological channels for order to be created, for complexity to be created.

0:36:11 SC: And in some sense they're fragile. There's sort of unique ways or almost unique ways for complexity to come into existence and build upon itself. And I'm not characterizing that feature as perfectly as I could, but maybe you know what I mean. And maybe you can do it better, but then this opens up the possibility for catastrophe. It's good that it builds this complexity so effectively, but it's bad because it also opens the possibility for being wiped out.

0:36:41 KJ: Yes, yeah, I think it's very much a double edged sword. But given that, it strikes me as interesting that nevertheless complexity has increased steadily over the evolution of the universe. And so, although in theory, it can be [0:36:57] ____ as thought as increased. Nevertheless, it has generally gone up, but something that you said in your talk, which made me kind of pause and contemplate the future, gloom-ly, is that complexity inevitably, as the universe unfolds over the next umpteenth billion years is going to go down again. And if I understand you correctly, the reason is to do with entropy. But I'm not fully sure I have a handle on why. So, can you unpack that a bit more?

0:37:33 SC: Sure. I think that this is not the kind of thing that makes us change our life insurance policies or even change our ecological policies worldwide. But it is true that this idea that complexity grows is one that can't last forever, at least it's true in the universe as we know it. Our universe is very young in some sense. Okay, it's 14 billion years old, which sounds old. And usually, when you watch a TV show like COSMOS, which explains you the history of the universe, that treats the Big Bang as the beginning. And today, as the end, like we're December 31st. Of course, that's not true. The universe is gonna keep going. And you can ask, how does the last 14 billion years compare to what comes next? We discovered in 1998 that the universe is not only expanding but expanding faster and faster, so there's no reason to think it will ever stop expanding, it will probably just keep expanding forever. But.

0:38:33 SC: A part of the universe we can see is only finite in size because universe is accelerating. There's a horizon around us past which you will never be able to see. So there's a finite amount of stuff in the universe, and there's an infinite amount of time for it to evolve. So like the cream in the coffee, it will reach equilibrium. It will reach a point where everything is smoothed out into its highest entropy configuration. Now, this takes a very long time. The oldest stars will burn... Or the longest-lived stars, I should say, will burn for trillions of years. We've only been around for 14 billion years and stars will still be shining a trillion years from now. But eventually, they will use up all their nuclear fuel. That's a feature of using up entropy. We'll use up all the hydrogen helium that we had to burn in the stars. And so the universal become dark, but it still won't be done yet. There will still be a difference between black holes, and planets, and stars, but eventually, even that difference will be smoothed out because all the stars and planets will fall into black holes, [chuckle] so we'll have the universe with nothing but black holes in it. And eventually, even that will go away because Hawking showed in the 1970s that black holes evaporate.

0:39:49 SC: So the black holes will evaporate into nothingness over a time scale of about 10 to the 100th years, one googol years in old-fashioned terminology. And then it'll be nothing but empty space, literally, forever. So there's no room for complexity in the heat death of the universe, 10 to the 100th years from now. Maybe there'll be some tiny ephemeral life forms that form in the evaporating black hole atmospheres, I don't know. That seems very unlikely to me, and very unsatisfying. It's certainly very different than what we have right now. But yeah, in some very real sense, we are in the part of the history of the universe, in the few billion years of history of the universe, where stars are forming, and shining, and acting is really robust entropy, low entropy, energy sources that allow life to exist, but that is, in some sense, a very temporary condition.

0:40:41 KJ: That's a very grim prospect. It's quite depressing [laughter] I don't know why 'cause I'm gonna be long gone myself.

0:40:47 SC: Trillions of years, trillions of years. Yes.

0:40:49 KJ: [chuckle] Still the idea that it cannot last forever. But again, it seems to be very woven up with space because if you think that the driver for complexity is the ability of systems to reach out in space and kinda grab entropy, if you like, from around themselves, it seems like space is expanding faster than they can do that, and eventually will expand beyond the realms of the possibility. So, for example, even if we manage to become a super civilization that could harvest energy from all around us and managed to stop ourselves from going extinct and all the rest of it, eventually the universe would just get so big that we couldn't find any of the energy anyway. It's too far away, and too little of it. Is that fair to say?

0:41:41 SC: Yeah, no, that's completely true. The way you can say it... I'm not sure that space is crucial in this particular case. What's crucial is entropy, again, in the sense that we have not reached the maximum of entropy that we can reach. So as long as we're not at our maximum entropy state, there's still room for something interesting to happen, for some complex structure to be there, and persist, and think, and love, and care, and die, and write poetry. But as you get closer and closer to maximum entropy, there's less and less room for anything complex and interesting to happen. So that's the ultimate fuel crisis of the world. Energy is conserved, but entropy is not. Entropy goes up. And so, the difference between where we are and thermal equilibrium just decreases with time. And so you're right. Eventually, there'll be no more room left. We'll have used up all of our, what we call, free energy, that's the technical term. The free energy will go to zero, yeah, and life will be over. And not only will they be no more living creatures, there'll no memory of you having ever existed, sorry. [laughter]

0:42:53 KJ: That's really a shame. Is there no way we can stop this like could an advanced technological civilization somehow stop this in theory?

0:43:03 SC: So I think the answer is no. And even in theory, you can't. You could imagine building something, a record. So I don't think it's actually possible but it's within the realm of conceivably that you could make an artifact that recorded your greatest deeds and lasted for an arbitrarily long period of time. But what would be impossible is for anyone to read that artifact because the act of reading and remembering increases the entropy of the universe, and if you're at maximum entropy, that can't happen. So, consciousness itself, thought, and life cannot exist once you've reached equilibrium.

0:43:47 KJ: But that's assuming that the second law is completely unchangeable. Is that the case?

0:43:57 SC: Yeah.

0:43:57 KJ: Could we ever wind the clock back?

0:44:00 SC: My money's on the second law yeah. There is something called the recurrence theorem that if you wait long enough, if you live in a universe where there's only a finite number of things that can happen, truly finite number of things that can happen, not just that we can observe, and then you will fluctuate back into a low entropy state. But that causes all sorts of problems with things like Boltzmann brains and things like that, and it doesn't... It seems to very clearly not be the universe we actually live in. So I don't think that that... Not only is it not the universe we live in, but it wouldn't really ameliorate your problem because you couldn't send messages from one part of time to another through the point of equilibrium. So not a lot of room for talking to your future friends.

0:44:43 KJ: Could we find a way to borrow from here into an adjacent universe that's still in a very low entropy state and borrow some of their entropy?

0:44:52 SC: Not according to any laws of physics that we know about them. This is good to think about if you wanna... This is very long-term planning. The long now would be embarrassed about how short-term their thinking compared to this.

0:45:04 KJ: I'm grasping at straws here.

0:45:05 SC: Yeah, no, I know. But it's... As far as I know, no. So what is possible is that a new universe will be born from ours, that a baby universe will be born. Again, no information will be conveyed from us to them but it's possible that what we think of as the universe is just part of a bigger multi-verse and more universes are constantly created, and the way that those universes are created naturally starts them in a low entropy state from which they can grow and things can happen and in fact, it's very possible. In fact, I proposed a theory which this is true, that our universe came from a pre-existing universe in exactly that way. But again, they can't talk to each other as far as anyone knows. That's the downside, yeah.

[laughter]

0:45:51 KJ: Yeah. Very very impressive. So can I ask you another question then something I've been trying to understand. So a lot of these processes that we've talked about, for example with the cream and the coffee, or the converse which seems to be a creation of order which is oil separating from water, these changes in complexity linked with entropy seem to depend on gravity, and in fact, everything seems to depend on gravity. So, the formation of stars and planets and life, it's all dependent on gravity. To what extent is gravity a fundamental part of this or is it not?

0:46:40 SC: Well, I think that it's part of a fundamental part. Let me very briefly mention that oil and water separating actually increases entropy as that happens, which it must because entropy increases. But that's because of detailed chemistry properties of hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules in the oil that it's actually a higher entropy configuration for them to be not mixed than for them to be mixed once you go into details.

0:47:03 KJ: Sure. They need gravity for the oil to be on the surface?

0:47:09 SC: Well, even if you didn't have gravity, the oil and water would still separate from each other, but...

0:47:13 KJ: But they'd form globules.

0:47:14 SC: Yeah, they'd be in globules. So gravity does have that effect of segregating or stratifying or whatever it is, things in certain ways, but it's only because there's also other forces, So I think that what is important is not gravity per se, but the fact that there are different forces that work in different directions, so there can be a competition between them. That's when things can become interesting when you're looking for an equilibrium between some push and pull of gravity trying to push things together. And let's say, electromagnetism pushing them apart. That's the fact that we have these two forces that both act over long ranges in the universe, gravity and electromagnetism, seems to be a minimal requirement for really interesting complex structures to form.

0:48:00 KJ: Okay. So again, that's that being able to reach out in space and time is a prerequisite for complexity, and I guess you could think of the role of gravity as being to bring things together, to move things through space so they can interact in ways that they couldn't have otherwise. Is it...

0:48:22 SC: Yeah, absolutely, but you know gravity is subtle also. Even at the physics level, which I keep saying correctly is way more simple-minded than the biological level. On the one hand, gravity pulls things together. On the other hand, it's also the expansion of the universe. It counts as gravity. That's part of the geometry of spacetime which Einstein told us is what we think of as gravity. So the fact that the universe is accelerating and eventually pushing things apart is also gravity. So the thing we don't understand cosmologically is why the universe started in such a low entropy state with 10 to the 88th particles stuck into a region the size of a cubic centimeter which seems absurd, and then everything expanded and cooled from there to be billions of light years across. But it's all gravity that does both those things. So gravity is your friend for a little while, but then it's ultimately your enemy if you wanna be a complex structure.

0:49:22 KJ: Okay. I didn't know that gravity is driving the expansion of the universe. Can you explain that to a non physicists.

0:49:29 SC: Yeah, there's two senses in which that's true. One is just a very, very blunt sense in which the size of the universe changing over time, one way or the other, is a gravitational phenomenon. Einstein back in 1915 explained that what gravity is, is the curvature of spacetime. And in a universe that is more or less uniform through space, one of the features of what we call the curvature of spacetime is the changing size of the spatial universe. The scale factor as we call it in general relativity that tells us the relative distance between distant galaxies. So the fact that galaxies are moving apart from each other, they're not moving through space. Space is growing and that is a phenomenon due ultimately to general relativity which is the theory of gravity. There you go.

0:50:22 KJ: Okay.

0:50:23 SC: But then there's the extra new feature that at least in the old days even though the expansion of the universe was part of our gravitational theory of general relativity, at least gravity was attractive. At least it was slowing down. But in 1998, when we discovered the acceleration of the universe, we realized that there is probably something that we call the vacuum energy, the cosmological constant which is pushing things away. It's still gravity. It's not a new force. Sometimes people say we discovered a new force of nature but that's not right. It's the old force, gravity, the first force we ever discovered. But there's a new kind of stuff the vacuum energy whose gravitational effect is to push things apart. So, there you go, even gravity can have tricks up its sleeve.

0:51:08 KJ: So trying to link this to entropy then. So I still kind of think of entropy as somewhat bound up with space. So, for example, that's the gas molecules that are in half the box versus the whole box, and the probability of finding one of those molecules in a particular place and so on and so on. So if you suddenly doubled the size of the box and all particles were on the one side, then as entropy unfolded, they would spread out across the box. And naively, it feels to me that the more space you've got, the more microscopic configurations are possible. So does that mean...

0:51:48 SC: That's true. I would agree with that, yeah.

0:51:50 KJ: The expansion of space is somehow tied up with how much entropy is possible?

0:51:56 SC: Yeah, well, it's slightly tricky. I wanna say yes, but I wanna then put a footnote. The thing that is a little bit hard to internalize is that the expansion of space is part of the physical system. So, when you say, how much entropy is possible, you really shouldn't fix space at a certain size. This is just a feature of general relativity. You can always make space bigger. That's one of the things that can happen. So unlike good old classical statistical mechanics when you would talk about putting gas in a box and fixing the boundaries of the box, if your box is the universe you have to allow the box to expand. That's just part of the dynamics. So when we say that in the early universe, there was a cubic centimeter where all the particles that we now see in the universe were somehow confined in a relatively smooth distribution. It's not quite legit to say, "Let's calculate all the ways we could arrange those 10 to 88th particles inside a cubic centimeter and compare them to how many ways we could arrange the particles today and say that the possible entropy has gone up."

0:53:10 SC: Because among the weird things about that initial condition is that it was small, within the cubic centimeter so you can't separate out the arrangements of the particles inside the box from the size of the box itself. So the lesson is still true that yes, the entropy was very low back then, it is much larger now, but it's not that the allowed entropy went up, it's just that we weren't ever coming close to accessing the allowed entropy of that early time.

0:53:42 KJ: So what determines the allowed entropy then? If that doesn't change... If you can't... You seem to be saying that it's not meaningful to say, to talk about the number of ways that you can arrange all of those particles in that centimeter.

0:54:00 SC: Well, you can talk about that, but you can't say that's the maximum entropy, right? Because you could say, "Well, but I can make the box bigger and there's even bigger entropy allowed to be.

0:54:09 KJ: So, I see the problem. So, I'm thinking, I have two reference friends in my head at the same time. One is the centimeter square universe with all the particles jammed in and unable to move. So therefore, low entropy 'cause you can't rearrange them.

0:54:24 SC: Where can they go? Yeah.

0:54:25 KJ: And then the other one is a large universe where the could be all over the place and that feels like there's a lot more ways that you could do that and that's a very high entropy, but are you saying that it does not...

0:54:35 SC: All that's completely correct.

0:54:37 KJ: You can't have those two reference frames at the same time.

0:54:39 SC: Well, you can't... What you can't say, sorry, there's yet another subtlety, here. Here's yet other subtlety. When matter is extremely densely packed as it was in the early universe, gravity, not just over the expansion of the universe, scales, but gravity, the gravitational pull of the particles on each other was really important. It's very densely packed. That makes perfect sense. When matter is very densely packed, high entropy doesn't mean smooth anymore. In a box of gas, a high entropy configuration is a smooth uniform configuration, but when gravity, when the mutual gravity between the particles becomes important, you increase entropy by making things lumpier.

0:55:32 SC: Like in the current universe, you could make a black hole, the black hole, the center of our galaxy has more entropy than all the particles in the known universe. So the fact that the entropy was very, the configuration was very smooth at early times is itself a low entropy fact. It's not only that everything was packed into a tiny region of space, which is true and low entropy, but also it was smooth which is low entropy.

0:56:00 SC: So cosmologists, some of my best friends, professional cosmologists have this idea which is 100% false that the early universe had high entropy, because they say, "Look, it was smooth and it was hot and it was glowing like a black body, it looks like it was thermal equilibrium, it looks like a box of gas." And that's entirely wrong because both it was a very small box of gas and because it was smooth even though gravity was important. So it was an anomalous low entropy state from any way you slice it.

0:56:32 SC: So then it's been increasing ever since, and we're gonna keep increasing and it's fascinating and it's full employment for I think physicists and biologists to study the specifics of the ways in which it's increasing. So, cosmologists will talk about forming black holes and then evaporating and biologists will talk about all of these complex structures acting as entropy engines. That's what life does, in some sense.

0:56:57 KJ: Yeah, yeah. I mean, life... I was interested in Schrodinger's idea of life as being a sort of temporary reversal of entropy. I came across that concept a long time ago, and always it's always struck me as... Not obviously wrong, I think he didn't accept it, he didn't... But at the same time, it did always plant this idea, why does life do that? Why did the universe not just drift out and defuse? And not only has it formed but it continues to do more and more and more crazy and interesting things. I just think that's amazing.

0:57:38 SC: Well, I think, here's one way of that I think about it, but this is very primitive and we should be able to do better. The space of possibilities is really large. When you have a lot of particles and there's a lot of places they could be in the universe and there's a lot of ways they could interact with each other and so forth. There's a lot of things that can happen. And the journey from the early universe where entropy was low to the very, very late universe where we're in equilibrium is one of exploring that space. Because in equilibrium by definition, there's sort of an equal probability to be in any configuration, but just because the set of configurations is so big.

0:58:17 SC: You're not actually even in the 10 of the 100th years that it takes the universe to equilibrate, you're not gonna come close to actually exploring every single arrangement of stuff within that universe. So it's easy to say, "Sure, you explore more and more of the allowed Face Base or whatever it is, but the way in which that happens specifically is the crucial question when it comes to life and complexity and things like that." And there, I think you keep correctly emphasizing space matters because life is an organized by itself low entropy thing that can exist only because it's increasing entropy elsewhere, in space, in some sense.

0:59:01 KJ: Yeah, yeah. The reason that life can do that is because of the spatial properties of the Carbon atom, because of its three dimensional symmetrical structure, it's able to build these amazing molecules that can reach out and make these, as you noted, these interactions across space and time. So without carbon we wouldn't have all of those. And I find myself often wondering whether this has ever happened anywhere else. I used to assume that it must have in many places in the universe. But as time has gone on, and I started to think, actually, maybe it's never happened anywhere else, maybe this is really unique, the particular conditions that have allowed carbon-based life to form and remain stable. Maybe that's so unusual as to be unique.

0:59:51 SC: Well, I think I've had that thought also. And my attitude is, we don't have any data here, we don't have a lot of data about the fraction of other planets or other environments that have life on them, so we should be very open-minded, maybe within our observable universe the earth is the only planet that ever had life form on it. There's certainly another option, which is that since life seem to catch on pretty quickly on earth, but multi-cellular life took a very long time to form or eukaryotic life or something like that took a long time to form. Maybe those are the hard parts. And when we visit other planets there'll be some sort of single cyanobacteria all over the place, but nothing more interesting.

1:00:36 KJ: Yeah, well, they probably think they're interesting and they've been a lot more successful than we look like we're gonna be.

1:00:43 SC: Maybe, maybe. But you bring up this question of the necessity of carbon. So I wonder about that too. Obviously, carbon is crucial for life as we know it, but are we just so Chauvinistic about that? If the chemistry of carbon were completely different, I'm open to the possibility that life could have formed in some very bizarre to us but very different way.

1:01:04 KJ: Yeah, I don't know enough biochemistry. No, I think there are one or two other atoms that might have the structure or the ability to form the Tetrahedral bonds and so on. But it's these long stable polymers that carbon can conform that enables us to grow these incredibly complex little machines that constitute all the enzymes and things.

1:01:31 SC: If we were very advanced, if we were max type mark, we would wonder about could life exist if space were one-dimensional versus two-dimensional versus three-dimensional versus four-dimensional, which is fine to do, which is fun, but the answer always is that it can only happen when it's three-dimensional, and I just really worry that we're being blinded by our the noses in front of our faces. When it comes to that. We know how it works in this case, we can't see how it would work in other cases, but I'm a little bit more skeptical that it couldn't just 'cause we don't know how it would.

1:02:03 KJ: Yeah, one thing we do know is we don't see any signs of it, when we look into the cosmos. So, if there is other life, it's not gotten sufficiently advanced to be able to make signals that we can detect.

1:02:17 SC: That's right. We wouldn't know. The current... Correct if I'm wrong with but the current state-of-the-art is we wouldn't know if all the exo planets we've ever seen are covered in cyanobacteria, right?

1:02:27 KJ: I'm not sure, why would we not know that?

1:02:30 SC: Just the current state of the art doesn't give us a lot of information about the...

1:02:32 KJ: So we don't have enough spectroscopic information.

1:02:36 SC: I think that's it. Yeah, I think that the planets are faint compared to their stars. But before we get too crazy in our speculations, I do wanna bring things a little bit down-to-Earth again because it's easy for me to say that complexity comes and then goes. And I think you very correctly want to emphasize the non-smoothness of that evolution over time, in the real world. Can you say a little bit more about the origin of these catastrophes? I know that there's specific catastrophes that we know about. Are there general features of catastrophes that decrease the complexity of a system, at least biologically if not more generally?

1:03:20 KJ: Well, I think the catastrophes that have occurred for life on earth, in fact, there have been quite a few. Paleo biologists have identified five major extinctions, but actually... I mean, extinctions are happening all the time. And sometimes extinction rate increases and decreases, but there have been a few really big ones. Some of these have been contributed by changes in the earth itself. So massive volcanic activity and so on. But the ones that interest me are the ones that were due to life, something that happened in evolution that suddenly changed the distribution of life. So, I think probably the first really notable one was the great oxygenation event that really completely changed the Chemistry of Earth.

1:04:10 KJ: And then there was the Cambrian substrate revolution that I mentioned, when life forms discovered how to move. And then how to burrow through the substrate. Another big one that was quite surprising to me is that when life came out of the oceans and onto land and trees formed, suddenly there was a massive increase in photosynthesis and a pulling of carbon dioxide out of the air, and that plummeted the temperature of the Earth and created an ice age. And then, of course, there's the one that we're doing now, we're completely changing the chemistry of the planet and we're seeing a massive extinction, and again, that's because we've managed to proliferate enough to have global effects on the planets chemistry. So those, I find those quite interesting, worrying but interesting. Because this is life exploring the parameter space and then every now and then it finds itself in a dead end.

1:05:12 SC: Yeah, I think that the lesson of all of your examples is that these catastrophes were all driven by progress, right? Like life discovered a new way to do something exciting, and fun, and did it a little bit too enthusiastically, right? And then lead to the extinction of a whole bunch of other life forms.

1:05:29 KJ: Yeah, yeah, so you can... When you develop a new ability to extend your reach in space and time, some... That'll lay general [1:05:38] ____ sorts of paths. And some of those paths will lead you to bigger and greater things but other paths will lead you to catastrophe. Evolution is full of dead ends and we can't tell in advance which is gonna be the dead ends and which are not. But we're particularly interesting because we, as far as we know, are the first species that have been able to know this and to contemplate our future and the possible regions of the space that we can explore and to make choices theoretically, but the question is, does the dynamics of our interactions among ourselves, allow those choices to be made or are we condemned to just follow this path that's gonna lead us off a cliff? And I don't, I don't know the answer.

1:06:34 SC: Yeah, I think one way of thinking about the evolution of life is not only an evolution of complexity in terms of the structures that make the physical organism but an evolution of the sophistication with which we deal with information. Right? The first RNA or DNA molecules actually carried some information and that was crucial, obviously, and then there was this sort of differentiation of information when you got to eukaryotic life and there's mitochondrial DNA and nuclear DNA, and so forth. And then multi-cellular life, there's more differentiation. And then when the brain came along and the nervous system, you could think and you could have self-awareness and now that we have language, you can think symbolically and these are all information processing leaps forward. So, I think there's another wonderful frontier in science is to think about insights from information theory and how they relate to physical evolution, both of the universe and of the biology within it.

1:07:37 KJ: Yeah, yeah. Oh, one of the things that fascinate me about that is the equivalence that's been made between entropy and information.

1:07:46 SC: Mm-hmm.

1:07:47 KJ: In some sense, as these information processing engines, if you like, brains, are performing their own entropic manipulations by virtue of how they operate in different domains at the chemical level but also, this kind of more abstract level which I think is fascinating.

1:08:07 SC: Yeah, no, I think it's absolutely... Like I said it's gonna be full employment for future scientists because in some sense the way I like to think of it is... Well, let me back up a little bit because people get confused when you talk about entropy and information because information theorists define the relationship between entropy and information in exactly the opposite way to how physicists define it because information theory grew out of Claude Shannon talking about how to send signals over wires, and you send information more efficiently through a code that is high entropy because high entropy means you don't know what letters come in next. Every time you get a letter you get some new information that's very useful, right?

1:08:54 SC: So, information theorists or communication theorists like to link high entropy with high information content. Whereas a physicist, who thinks about the cup of coffee, not a message over the wires says, "if I'm in a low entropy state, if you tell me that you're in a low entropy state, then I know a lot about what state you're in because there's only a few of those states that look like that. So I have more information about the system when it's in a low entropy configuration." And I think that for this discussion that we're having right now, it's that definition of entropy that is more germane. I think that in some sense because the universe started in a very low entropy state, it started with a lot of information in some sense built-in and all we've been doing... We haven't been increasing the information content of the universe by having life or thoughts or books, we've been degrading it, because entropy is increasing, but we've been using, manipulating, taking advantage of the fact that entropy... That information is all around us in more and more interesting ways.

1:09:57 SC: So breaking the universe up into these sub-systems that manipulate information is a wonderfully truthful way I think of thinking about life and species and evolution.

1:10:06 KJ: Right. So interesting is another way of saying complex, I guess.

1:10:12 SC: Yeah.

1:10:12 KJ: So you could say that the universe started off with a lot of information, but not much interest.

1:10:17 SC: That's right.

1:10:18 KJ: And now it has less informative but more interesting, is that fair to say?

1:10:22 SC: Yeah. And I think this is something that you get at with your questions about space and interactions and things like that because the universe as a whole increases in entropy and decreases in information but it gets shuffled around in interesting ways, and certain parts of the universe like you and me, can hopefully take advantage of the overall degradation of information around us to make life interesting as we go.

[chuckle]

1:10:48 KJ: I feel like we are living at an optimum time in the evolution of complexity in the universe where it is maximally interesting and...

[chuckle]

1:11:00 SC: Well, they might have said that 10,000 years ago too, so but...

1:11:02 KJ: That's true.

1:11:03 SC: 'cause they didn't know, right?

1:11:03 KJ: The question is are we at the top of the hill, or is it, can we still climb a little bit higher?

1:11:08 SC: Well, I think that what you have correctly pointed out, is that there's no inevitability in this increase in complexity. Like sure, maybe there's a trend made there's a tendency but there's also this very definite empirical record of catastrophes, right? And so when you see a stumping carbon into the atmosphere and the sea levels rising and stuff like that, don't be sanguine that, "oh yeah, life is resilient and everything will be okay." We could hurt it really badly.

1:11:34 KJ: Yeah, that's a very good take-home message.

1:11:38 SC: Are you optimistic overall, about how we're gonna do?

1:11:41 KJ: Not optimistic, but hopeful. Is that possible?

1:11:44 SC: Hopeful. [chuckle]

1:11:46 KJ: I like to think there is... There are things we could do, but if you gave... If you asked me to put a probability on it, I'd probably have to say it was low-ish.

1:11:54 SC: Low-ish. Well, yeah. Well, I hope not, but all we can do is... Lessening the probability is less important than trying to increase the probability.

1:12:05 KJ: I completely agree.

1:12:06 SC: I think that's the thing to do, alright.

1:12:07 KJ: I think if any species can do it, then it's us.

1:12:10 SC: There you go, let's put it that way, I like that. The cats are not gonna save us, believe me, I have two cats and they're not gonna stop global climate change in any way. Kate Jeffery, thanks so much for being on the podcast. It was tremendously fun conversation.

1:12:21 SC: Thank you very much.

[music]

She is amazing! What an intellect. I love this podcast. She asked the questions of you that I would if I was smart enough to form them. Thank you for sharing this.

fantastic podcast

Fantastic Transcript!!

Great discussion…I’m most interested in the philosophical implications of this, some of which you touched on at the end, the relationship between entropy and information. Also the implications for natural language and communication (also information), and how our (human, and thus contingent) identification and definition of macroscopic states may be analogous, in the arena of language, to the differentiation and observation of said states. Seems like all these processes are informational exchanges of some sort or another.

I just listened to the beginning of this so far.

I believe that the answer Dr. Jeffries’ question of why a DNA strand of random nucleotides or of degraded DNA would have different entropy content from a DNA strand with genes containing the information to make a viable organism is that entropy also applies to information content.

I need to go back and look at this, but I took Melanie Mitchell’s Introduction to Complexity some years ago, and I think entropy applies because there are many more ways to send a signal with little or no information content than a signal with large information content. There are many more ways for a strand of DNA to be “nonsense,” or a series of random nucleotides, than there are ways for a DNA strand to contain information. So, I think that means that a DNA strand with little or no information content has lower entropy than a DNA strand with information. (I hope I have this right. I have learned much of what I know about entropy from you as well as from Melanie Mitchell, but I am always having to review which is high and which is low.)

Oh my goodness I am so sorry I got her name wrong.

Right on. Another personal favorite, right up there with Kate’s and Michele’s and a couple of others. But then I’m a bioengineer, analytical and applied, interested in future and big picture issues, so I’m biased. lol

Sean, still hoping here that one of these days, you’ll get around to expanding on your “poetic naturalism” and related ideas – even if it’s just along the lines of creative philosophizing or the like as Sagan for eg would do. I can’t help but think it points to a new kind of framework with infrastructure, along with new exciting, energizing inventions and innovations, one that’s science informed, science abiding and science respecting. Yay!

Obrigada, Sean Carroll, e, Kate Jeffery

Outro episódio espetacular!

É minha opinião que deveria haver uma maior “ligação”, discussão, proatividade entre as vareas subareas da ciência! E, filosofia da ciência!

À semelhança deste episódio!

Obrigada

The concepts around entropy and the arrow of time fascinate me. “From Eternity to Here” is one of the best books I’ve read. What intrigues me the most is the use of the “past hypothesis” to overcome “Loschmidt’s paradox” which in the way stated is a mere “turtles all the way down (to the big bang…) kind of tautology.

More than anyone else, Kate Jeffery made you “define your terms.” That’s what good philosophy is all about.

“The cats are not going to save us.”

No. No they aren’t. We’re the ones. Let’s go

subjective entropy I really tease out and bother me could any one talked about it?

and i dont understand why expansion the universe cause the increase entropy of the universe!

Strictly speaking, entropy is a property of a set of quantum states (spec. the log of the number of those states), not a property of a single quantum state; and the universe at any moment is in a single quantum state; therefore the universe does not have an entropy.