The internet has made it so much easier for people to talk to each other, in a literal sense. But it hasn’t necessarily made it easier to have rewarding, productive, good-faith conversations. Here I talk with sociologist Rod Graham about what kinds of conversations the internet does enable, and should enable, and how we can work to make them better. We discuss both how social media are used for nefarious purposes, from cyberbullying to driving extremism, but also how they can be mobilized for more lofty goals. We also get into some of the lost nuances in conventional discussions of race, including how many minorities are more culturally conservative than an oversimplified narrative would lead us to believe, and the tricky relationship between online discourse and social cohesion.

Support Mindscape on Patreon.

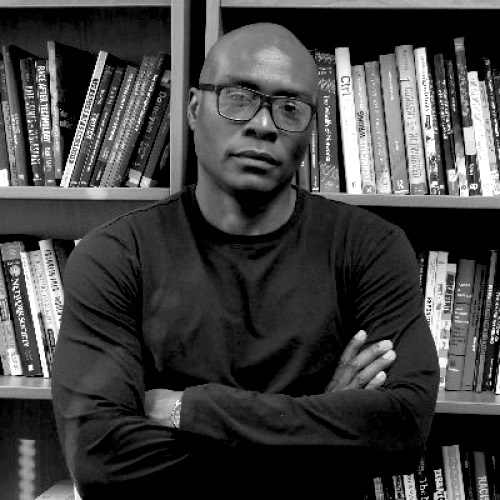

Roderick Graham received his Ph.D. in sociology from the City University of New York. He is currently an Associate Professor of Sociology and Criminal Justice at Old Dominion University, and serves as the coordinator of the university’s Cybercriminology Bachelor’s program. He is the author of The Digital Practices of African-Americans.

[accordion clicktoclose=”true”][accordion-item tag=”p” state=closed title=”Click to Show Episode Transcript”]Click above to close.

0:00:00.6 Sean Carroll: Hello, everyone, and welcome to The Mindscape Podcast. I’m your host Sean Carroll. This thing that is going on right now, right this very second as you’re listening to my voice in some device, is enabled by technology, right? There were no podcasts 20 years ago. When I was a kid, we didn’t have your podcasts and so forth. The Internet, cyberspace, whatever you wanna call it, has enabled an enormous number of ways that people can communicate with or at each other that were simply unheard of before. You have not only podcasts, you have YouTube videos, you have social media, you have blogs and online magazines and so forth. The ability to communicate one way or the other is vastly larger… Or the capacity, I should say, vastly larger than it ever has been before. This does not, as many of you will be familiar with, necessarily mean that the quality of communication has gone up. In fact, it’s very clear that in some cases, in some circles, in some circumstances, this ability to communicate has been used to what we would think of as nefarious ends, to not communicate accurately or even good things, but to spread racism, spread disinformation, to recruit people into extremist groups and so forth. The radicalization of people from Facebook and YouTube is a common theme that we hear about in the media these days.

0:01:23.1 SC: So with today’s guest Roderick Graham, we talk about this tricky intersection of cyberspace and difficult social conversations. Roughly speaking, the podcast falls into two parts. We talk first about some of the research the Rod has done on cyberspace and cyber bullying, sex trafficking, ways that cyberspace has been used against people, and then ways that oppressed groups, or groups that believe they’re oppressed, often correctly, have been able to fight back. In some sense, Rod is a techno-optimist about these things. He’s very clear that technology has been used for bad ends, but he’s hopeful that it can be used for good ends. And it is being used for good ends, that people can find each other online in ways that they couldn’t before, that groups of not just minorities in the sense of racial or ethnic minorities, but tiny groups of people who would have been lost in a wider society before can find each other in ways they never could have.

0:02:23.7 SC: And in the second part of the conversation, which is related, I think, we talk about the idea that minority groups of people in particular can be oversimplified by other groups in sort of how they think about them. In particular, the example that we think about is how minority groups such as Black Americans, Latino Americans, and so forth, can be more culturally or socially conservative than you might guess from their economic progressivism. And that’s an important factor to keep in mind if you want to have productive conversations. We saw this in the 2020 election, that you cannot treat these groups of people as big homogeneous blobs. They’re different from each other. Someone in the same economic circumstances is going to be in different social circumstances if they are of different races, different ethnicities, and they react to those in different ways. So how do you reconcile being a little bit culturally conservative, a little bit socially or economically liberal and so forth?

0:03:18.9 SC: So these are all to the goal of having better conversations, having better conversations online, in person, harnessing these powers that have been given to us by technology to make our interpersonal communication a little bit better, and a little bit more productive, a little bit more nuanced than it has been before. So I think it’s a very important interesting conversation. Rod has many online interventions of his own. He’s on Twitter, he has a wonderful YouTube page that you can check out where he interviews people and he gives little short YouTube videos by himself. So check that out, all in the, like I said, the goal of making conversations better.

0:03:55.6 SC: Before we go, let me just mention something I keep forgetting to mention and I want to, which is that you know we have a webpage for the Mindscape Podcast, preposterousuniverse.com/podcast. And the reason I bring it up is because there’s a lot of goodies there, such as complete transcripts for every episode. This is something that is essentially supported by the Patreon supporters. We have enough money to pay a transcription service to write down every word. So, very often if you wanna search, you can search the Mindscape Podcast archives for words, and you will get every word that has ever appeared in every transcript of every of the episodes. We’re in episode 136 now, not including all the bonuses and so forth, so there’s a lot to search through. If you’re, I don’t know, if you’re bored, if you don’t have anything to do, or if you wanna think to yourself like, “Where do we talk about the measurement problem of quantum mechanics?” Things like that. It’s all there on the web page, preposterousuniverse.com/podcast. And that’s enough of that. With that, let’s go to.

[music]

0:05:07.5 SC: Rod Graham, welcome to The Mindscape Podcast.

0:05:10.2 Roderick Graham: Hi, thanks for having me.

0:05:11.7 SC: Let me begin this with a little bit of a preamble, because this is a slightly different topic than what we usually do, although who knows, ’cause we do so many different topics. What you do for a living seems to involve hot button issues over and over again, racism especially, but also issues about the Internet and social media that people have emotional opinions about. And I just wonder how that makes you feel in your every day life, in the sense that, you know, I can ignore many of these issues, I can choose not to talk about them, partly because I’m white, right? This is an aspect of white privilege, but also partly because I’m a physicist, so I could if I wanted to ignore these kinds of issues. But I think it’s important to talk about them, even though I know for a fact ahead of time that no matter what we actually say, the percentage of likes on the YouTube version of this will be lower than average just because we’re talking about issues that are very, very sensitive. So…

0:06:07.4 RG: Oh, that’s true. Yeah.

0:06:08.8 SC: As a professional who does this, do you ever feel like, “Wow, I’m just exhausted by doing this all the time?” I mean, it’s not just your everyday life, it’s your professional life as well.

0:06:19.7 RG: Well, you know what? No, not at this point. I really didn’t start doing this until after I knew that I would gain tenure.

0:06:27.7 SC: Okay.

0:06:28.2 RG: So even though I was talking about race, it was really couched within technology. And the way that I would talk about it wasn’t in any way that would make anyone go up in arms. It was really about how racial minorities, particularly Black Americans, could use technology to improve their lives. And then I started talking about cyber crime in general and how to protect computers and mobile phones. So it was not any hot button issues really until the last year or two that I really started doing this.

0:07:07.4 SC: And that’s in a more sort of public intellectual vein, in writing op-eds and being on Twitter and things like that.

0:07:13.8 RG: That’s right. That’s right. And it was an intentional choice. I felt that, I don’t know, I was losing a little meaning from doing what I was doing. I felt like I was gonna be stuck if I just tried to produce research, and who was gonna read that? So I said, “Well, let me try something else.” [chuckle] And that’s kind of how it started. Yeah.

0:07:33.8 SC: Yeah, and it actually makes sense to me. I think that there seems to be a connection, but let’s start with that old school research you were doing back before a year ago. You’re a sociologist. I think you’re the first sort of card-carrying sociologist we’ve had on the podcast. Is it accurate to say that the Internet and social media and cyberspace were the focus, are the focus, of your professional research?

0:08:00.7 RG: It is, even when I get around to doing research now. Certainly, yes. Yeah, so it started with dealing with racial minorities, then it migrated to deviance online, and so now I guess I would say, “Okay, I’m studying cyber crime online.” Yeah.

0:08:14.9 SC: Cyber crime online. So, I mean, this is… [chuckle] Even though you said it wasn’t, this is a hot button issue, right?

0:08:22.6 RG: [chuckle] A little, yeah.

0:08:22.7 SC: People really worry about the effects of cyberspace on the kids today, and the overall discourse and extremism. Have you found in your research any clarity on the big questions of whether or not the flourishing of social media and cyberspace more generally has made us better or worse communicators, people, citizens, fellow people?

0:08:49.1 RG: That’s an interesting question. I guess when I first started doing this, I was one of those utopians. I thought that, “Okay… ” And there are a lot of folks out here who think that technology is always a positive, or generally a positive, and I was one of those. I guess I still am a little bit. But I don’t know. I mean, given what’s been going on over the last year or so, I wonder. When I first started doing this, I guess, 10 years ago, it was important for disadvantaged groups and marginalized groups to have a voice, and so the Internet provided that. And we could see it. It was very visible. You could see all a sudden not just Black Americans, who I’m focusing on, but also women, Native Americans and Hispanics, and the queer community, they were able to get their words out through social media. And so yeah, in that way it’s great. But, I mean, these days you’ve got people running off into their echo chambers and you’ve got information flows that you could just say they are disinformation flows, they’re just not accurate. And people are consuming those things, and so now you wonder if it’s a positive or not.

0:10:06.7 SC: Well, what does it mean to do research in these kinds of areas? I mean, there’s no shortage of punditry about these things. So as the first sociologist we’ve had on here, what is your day-to-day when you’re trying to be scholarly about these questions?

0:10:22.7 RG: Well, I guess I could talk about my research. Now, it’s kind of weird, because the listener would be like, “Well, this guy started with African Americans, then he mentioned disinformation, and now he’s gonna talk about sex work.” But the research that I’m actually doing right now is about deviance online. So for this particular research, I’m doing sort of an empirical quantitative piece, where I’m trying to establish some overall human behavior patterns online. And then I’m doing a more interpretive piece, which is important for sociologists, ’cause we wanna get some sense of how people are living in their worlds, the meanings they associate with things. It can be a little gooey and icky. I know I’m speaking to a physicist, so it has to seem that way. It’s very imprecise, you can’t put it in numbers, but it’s important. So with this particular research, I’m trying to understand how men are using an online sex work forum.

0:11:22.5 SC: Okay.

0:11:23.0 RG: It is kind of a hot button issue because right now it’s illegal in the United States to put sex work… To sell sex online. And so this site is in the UK, and I’m studying this there because I’ve got my thumb to the wind and I feel like in a couple of years this will be something that will be a part of the public discourse. A lot of sex workers would like to be able to ply their trade, and they can’t. And so I want to look at the UK where it’s a little easier for them to do that and try and then make an analogy to what might happen in the US, if that makes any sense. So…

0:12:02.7 SC: It does.

0:12:03.1 RG: Oh, I’m sorry. Go ahead.

0:12:05.8 SC: I was just gonna say, it seems like a kind of good… What a biologist would call “a model organism”, in the sense that we can study this and try to get implications for elsewhere. It’s one of those examples, sex work, where something’s a little bit taboo, and you can ask how this new thing called social media is going to change our opinions about that.

0:12:24.2 RG: That’s right. That’s right. And so the quantitative piece for that is I did something that’s called a sentiment analysis, where you use a web crawler and you collect the words from a website, and then those words, generally speaking, have emotional valences. So, positive/negative. And so once you collect the words, you simply do a type of summative account and you get a sense of whether or not men are talking about women and just sex work in general in a positive way or a negative way. There are other types of emotions that are not in my head right now, but those are the two broad poles: Positive and negative. And so that’s one way, and I’ve already done that part. And it’s a very positive thing. It’s not as if… So, many anti sex work folks in the US are saying, “This is going to further objectify women.” That this will lead to some type of sexism. And so the idea is for me to see if that’s actually happening in the UK. And on this particular website, I don’t see that.

0:13:33.0 SC: That’s very interesting, because we all know that there is sort of a double-edged sword aspect to this kind of unfettered frontier of the Internet where people can say anything they want. And so what you’re saying is, it’s actually not completely Lord of the Flies. People are behaving a little bit better than we might fear.

0:13:51.6 RG: Yes, yes, and it might be that a lot of those fears just aren’t grounded in any actual evidence. So all the research that I’ve done or read prior to this show that it’s very little. It’s not as if you have a lot of men who are, one, looking to be violent towards women, to objectify women, and then going and finding a sex worker to do that. That does happen, of course, but that’s just not the general pattern. Or two, after they leave a sex work experience, do they all of a sudden become the types of people who would then objectify women? That’s not what I’ve seen. I’m about halfway through this research and I’ve got some more things to read, but I don’t see that at all. So the quantitative part is the collecting of the words, but now I have to go through and read the conversations online and try and interpret in a more nuanced way what men are talking about.

0:14:54.2 SC: Yeah, this seems to be my impression of how a lot of sociological research is done, that it’s a back and forth between the more quantitative, but kind of blunt instrument approach and then a more qualitative, that you can go in there and look at individual words and testimonies and try to see how that matches with the quantitative picture.

0:15:15.3 RG: That’s right, yes, yes. That’s a good way of describing it.

0:15:18.0 SC: And this extends, I guess, to other things besides sex work. I know you worked on cyberbullying. This is something where, again, there’s a bunch of fear about it. Do you think that the Internet or social media do give people a new and effective way to bully others, or is it just sort of something that’s been going on all along?

0:15:41.4 RG: Well, the last time I looked at the bullying rates, kids report bullying offline still more than online. But yes, but yes, it does happen. It does happen. From what I understand, as the scholars who study this, we’ve coalesced around some parameters for when bullying is really bullying. So it’s not just someone saying something nasty about you online. That doesn’t have the effects, the negative effects, that we often see with cyberbullying: Drop-out rates, using alcohol, drugs, some emotional problems. It has to be some things in place. And so one of those would be it’s gotta be repeated. A second is that there needs to be a power differential, where the person being bullied feels that they have no agency to do anything about it. And then third, it has to be perceived as bullying. So in other words, if a parent sees some words online about kids talking about her kid, it doesn’t matter if her kid thinks that it’s funny, it has to be a perception of bullying. So those three things matter, and when you get those three things, then you get those negative side effects. So that does happen. Yeah.

0:17:05.2 SC: And does this kind of research suggest things we should do about it? How engaged are you with the sort of policy prescription side of things?

0:17:16.8 RG: A few times I’ve done some public talks about cyberbullying, and the main way of dealing with this is just education of the parents. Sometimes parents go a little overboard with it. Also, educators can perform types of interventions, mainly by dealing with the bystanders. So if you can get bystanders to say, “No, this is not good,” and don’t pile on, then that deals with cyberbullying quite a bit. And then that agency part is important. So if kids know that they have someone to talk to, then that gives them a sense that they can do something about it. The worst thing is to just say, “Oh, just suck it up,” or just ignore it.

0:18:00.8 SC: Right. So in some sense it’s an example of the idea that you should fight speech with more speech. You can fight cyberbullying with cyber help or cyber neighbourliness or something like that.

0:18:13.5 RG: Oh yeah, that’s a good way of putting it.

0:18:16.0 SC: And we’re having this conversation at a time when there’s been a lot of recent conversation about free speech on the Internet and on social media platforms, in particular because some very well-known people have gotten kicked off of social media platforms. What does your research teach you about the pluses and minuses of completely unfettered speech? Or do you think that there are sensible ways to keep things in line or is that just a losing proposition?

0:18:47.0 RG: I don’t do any research on that. I have some standard, I think, sociological understandings of the harms of free speech. I don’t know where you stand on this, but there are a lot of folks who think that… They’re sort of free speech absolutists where it’s like, “Just let everyone talk, and the best idea will bubble up,” or as you said, combat bad speech with good speech, this type of thing. I’m actually not that way. For historical reasons, I think that people in the past have been able to use speech to denigrate groups, and so that has to be understood and we have to take that into account. And so that’s one reason. And then a second reason is, I guess, because of the cyberbullying research. I know that speech can hurt. Sometimes when I’m online when I wanna poke the bear a little bit, I’ll say, “Speech is violence,” or, “Words are violence.” And then that usually attracts some people and that gives me a chance to do back and forth. But I’m not just being silly. I think that words can hurt, and so I think we have to take that into account when we try and understand free speech.

0:20:02.5 SC: So I don’t think I’ve ever sort of written or even opined about this in any systematic way, but I completely agree that speech can be violence, but I’m also kind of a free speech absolutist in the sense that if people want to talk and other people want to listen to them, I think that should always be allowed, but I don’t think you should be forced to listen to things you don’t wanna listen to. I’m not sure if that makes me an absolutist or not.

0:20:29.2 RG: I don’t know. How would you take… Suppose… We’ve had these famous incidents of controversial speakers wanting to go on college campuses. That might happen more on your side of town than mine. I’m at a working-class university, so kids aren’t as politicized. But certainly I’ve seen it online. The speaker wants to talk, but the kids don’t wanna listen. So what do you do in that case? Are they justified in saying, “Don’t talk,” or what? I don’t know.

0:21:03.8 SC: Yeah. So my attitude is… And again, I’m very open to updating my attitudes about this ’cause they’re not completely well thought out. My attitude is, if something like a university invites someone to give a talk, then the members of that university, the students, the faculty, whatever, have every right to complain and say, “No, don’t do that. We’re stakeholders here, and we didn’t invite this person.” But if a little club at the university really wants a speaker to come and they’re not forcing anyone else to come and listen to it, no one is necessarily invited even, then I don’t think that other people who are not in that club have the right to shut it down.

0:21:43.0 RG: Oh, that makes sense. That makes sense. It’s really weird. If we were having this conversation four years ago, I would have probably said, “Oh, let the person talk.” ’cause I grew up in that era where words weren’t seen as these powerful weapons. But as I speak more with students and read more, I see it as just a change and a generational change. So I’m saying that I agree with you in the abstract, but I think that students, young people are perceiving the world in a different way and so I’m more likely to respect their perceptions up to a point.

0:22:25.5 SC: Sure. Right.

0:22:26.6 RG: So if they want to organize and say, “Look, we don’t want you on this campus.” Okay, I won’t stop that. Of course, if they wanna pass a law to stop someone to speak, then that would be different.

0:22:38.2 SC: Yeah, and actually, I wouldn’t be against them organizing and protesting, but if I were the organizer of the protest, I would say, “It’s a protest against what this person is saying, not a protest that tries to stop them saying it.” And again, this is where the double-edged sword comes in, because I worry that if you try to… Or if the norms change so that people can say, “Well, that set of people listening to that speech is itself bad, even if they want to listen to it,” that that kind of attitude will be used against fights for justice and trying to make the world a better place. It’s the people who are not in positions of power who are ultimately going to be more deleteriously affected by that.

0:23:27.9 RG: Yeah, I can see that. Yeah, that makes a lot of sense.

0:23:30.6 SC: So how does this come about? How does this play into the social media conversation about race? Which I know that we are gonna get to. I have my opinions about this. I think everyone listens to punditry about it, but in your view, how do you conceptualize social media as used by racists and anti-racists or non-racists?

0:23:52.9 RG: Oh, those conversations are terrible. They’re these bullet point… So I don’t listen to racists that much. I don’t know. They’re sort of hidden. They’re not in my network, so I don’t know much about that. But even the activists who are attempting to use a lot of the ideas from academia and use a lot of the words that bubble up out of academia, their heart is in the right place. So I’m with them in spirit, but not always in mind, because they’re flattening these very difficult terms and then using them to explain why they want social change. So it’s a bit weird. I do talk a lot about some of the words that you and your audience would know: White privilege, white agility, these types of things. And I realize that when I say those things, I have this iceberg, like the bottom of the iceberg that I’m taking with me when I’m talking and no one can see that and no one can know it. And Twitter with their, what is it, 250 characters or something, it’s really hard to get those things out. And then I’m coming in line behind several other people who’ve just simply said, “Okay, you have white privilege, be quiet,” which is not the right way to go. So you got people who are acculturated to responding to the bullet points, and me trying to use a slightly more nuanced bullet point and it just kind of goes downhill.

0:25:24.3 RG: I have to say though, I have been able to develop some pretty rewarding conversations with people after I do the blocking and the muting and the focusing on certain folks, who are not anti-racists. They don’t like the way that a lot of these ideas are used, but they also want racial equality, and they’re also concerned about transphobia, they’re also concerned about sexism. They just don’t articulate their concerns or see the way forward in this current anti-racist zeitgeist, I guess.

0:26:00.3 SC: Right. I guess, we can skip forward a little bit. This was all on my list of things I wanted to talk about, but you’re bringing up the idea that there can be productive conversations even online, even in the very limited domain that Twitter gives you. And I think that sometimes that gets lost in hot button issues because the noisy voices that might be very blunt and non-nuanced, drown everything else out. And it’s difficult to sort of screen those away and try to have a productive conversation with someone who disagrees with you, but in a potentially productive way.

0:26:39.1 RG: That’s true. That’s true. The bigger your Twitter account is, and yours is quite large, it becomes almost impossible. Mine is a moderate size, it’s not that big. So I can identify people who I have been having conversations with for quite a while, and we’re not really bothered that much after the first flurry of replies go down, and we can have a nice back and forth in between cooking dinner. It’s not bad.

0:27:08.7 SC: And this is something where you would say in your techno-optimist persona that has been enabled by social media? You wouldn’t be talking to these people otherwise, right?

0:27:18.5 RG: That’s correct. That is correct. So in that way, it’s been wonderful.

0:27:23.7 SC: Maybe this is not a research-level question, but do you have advice for people out there on social media about how to engage with people you disagree with?

0:27:34.4 RG: I do, and I don’t follow these rules all the time, but yes, I do. I think that people tend to respect respect. So especially in an era where there’s so much disrespect, you stand out. So when I had a really small account and I was like, “Okay, I’m gonna communicate social science now.” I started out as so respectful, people were like, “Whoa, this is refreshing,” [chuckle] ‘Cause I would have these kind of back and forth and I would try and explain things. And then what would happen is more and more voices would come on who I thought were very… That were kind of communicating in bad faith and the anonymous accounts and whatnot. And so they would wash out… I mean, they would just beat all that respectfulness out of you. And so you just would… I became a bit more coarse, but I still like to communicate with people. And if you can speak, if you can maintain that sort of level of respectability and good faith discussion, people will latch on to that.

0:28:35.7 SC: Yeah. No, I think that’s really, really important, but I think probably the most important thing in my mind of what you just said is just emphasizing how hard it is. To me, social media are wonderful in many ways, but they’re just such natural places to be snarky and short and extremist. And constantly reminding yourself to sort of engage with the potentially good parts is hard. And I try to do it and I’m not very good at it and I’m trying to get better.

0:29:05.3 RG: Right. Even though I can’t understand what you would be saying that would cause someone to say anything negative, but yeah, I guess there’s nothing you can say on Twitter when you have enough people following you that they’ll all agree with.

0:29:20.5 SC: Well, it’s very strange. There are people who are very emotional about the multiverse or quantum mechanics, but it does not compare to racism or sexism or things like that. And I’ll sometimes comment on those, and then you gotta block some people and decide who else is worth talking to.

0:29:35.2 RG: Yeah, yeah, I agree. Twitter is anonymous, or you can be anonymous, and that just naturally leads to changes in behavior. I think psychologists call it deindividuation or something, disinhibition, one of the two, or maybe both. And so it’s just a natural thing, when you can be anonymous and communicate with a 1000 other people, that you’re just gonna be nastier.

0:30:00.4 SC: Yeah. And what is your opinion about the idea that some of the algorithms on social media, either intentionally or unintentionally, drive people towards more extreme content, maybe just to get more clicks? This seems to be from the research I’ve seen a real phenomenon that maybe we should worry about.

0:30:17.6 RG: For a long time. Even from the… So you’re talking about Twitter now, but I can remember several years ago, people were complaining about the Google search algorithm showing different results, based upon your prior results or who they think you are or something. On the one hand, I’m like, “Look, those are private companies. They should be able to do what they want.” On the other hand, there are some negative consequences to that. I think it does produce some negative… I’ve seen several research projects which looked at the effects of how long someone has been on Twitter or social media and then their views, and I think it’s pretty clear. I hope someone doesn’t listen to this and say, “No, he’s wrong.” But I think it’s pretty clear that consuming a lot of social media does make you more polarized. So that’s a problem. It could be that the public outcry to these things has led to a lot of these social media companies changing the way they do things. I like the way that Twitter now has that news fact check thing that pops up when you wanna retweet a news story. And I think that’s wonderful. I think that those types of things over time will have us tame this technology.

0:31:33.6 SC: Yeah, I think that there are strategies, and that is an encouraging thing. I was actually even more than Twitter, thinking about Facebook or YouTube where there are recommendations for things to read. And we all know the more extreme stuff is more likely to get clicked on and capitalism gets in the way of trying to fix that, but it’s something we should probably keep in mind.

0:31:56.6 RG: Yeah. That’s right. That’s right. On the other hand, if I may throw a little counter example up there…

0:32:01.3 SC: Yeah, please.

0:32:02.2 RG: I spent some time in the manosphere on YouTube. It’s these channels that cater to men, and I think men spaces are needed. And so I was like, “Well, let me listen to these male YouTubers.” And they’ve got all types of acronyms that they use to describe themselves, MGTOW, and I forget some of these other, Men Going Their Own Way is what that means, and all these different types of self-identifications. So about a year ago, people started complaining that, “Okay, these sites are producing misogynistic content.” And I think that they do. I agree with that to some extent. And if you start… Getting to your point here, if you start watching one person talk about how to be a man in 2020 or something, it’s gonna lead you down a rabbit hole to eventually, “All women are bad.” That’s just gonna happen. And so the folks who were complaining about this had a point, and so I started hearing a lot of those male YouTubers talk about the great purge, about how YouTube was gonna deplatform them or demonetize them. And a lot of them did get demonetized and a lot of them had to leave YouTube because of that.

0:33:20.1 RG: And so I’m saying all that because it’s kind of a double-edged sword. If you say, “Oh, these algorithms are bad, they’re leading people down these extremist rabbit holes,” if you change those things, then all of a sudden you’re in a way determining what people get to watch. So it’s either way. You’re gonna do the algorithms to give them more stuff they want, or you’re gonna do an algorithm that doesn’t. But either way, it’s gonna be something. So it’s… I don’t know, it’s a double sword. I’m generally in favor of not extremism. I’m just kind of playing with the idea here, since you brought it up.

0:34:00.2 SC: No, I think it is very complicated and subtle, which is why my own views are not very set in stone. I would rather let all of these groups of people have their spaces to have their discourse. I think that’s very, very important. Maybe the most important thing is to provide alternatives where you can talk about manliness or whatever it is in a way that does not ultimately lead you to, “And women are bad,” right? [chuckle] And that’s a lot more positive strategy one could imagine taking, but also maybe more difficult than just deleting some accounts from YouTube.

0:34:32.7 RG: Right, right, right.

0:34:34.2 SC: And on the flip side of things, I think that you’ve written about the idea of Black people in particular, but maybe other groups using… Putting social media to work in a positive way. Organizing, finding each other in ways that they couldn’t. Would you say that there are senses in which social media have been forces for justice in recent years?

0:34:58.6 RG: Sure. On balance, I think that minority groups have been able to use social media or leverage social media to a greater extent than majority groups. I think so. That’s my general take on things. So my early research had to do with several of these dynamics. One was the ability to get ideas out from a sort of… It’s been a while since I’ve used those terms, but it’s a sub-space of ideas. You develop those ideas as a group, and then they become a part of the mainstream over time after they’ve been well-developed, which is kind of a phenomenon where you… Someone, you’ve got a collection of… Black Twitter is one of the prime examples. And so you got some main people in that space, and then they generate an idea about a problem in the world. And then other people in that space, they get to see how that problem is articulated, and then they talk with each other and they refine that articulation, maybe saying, “Oh yeah, you might be right about this. Here is this study,” or, “Here is this example and here is that example.” And through this kind of iterative process, you go from this inchoate idea to possibly, “Okay, this is the problem that we’re having and this is how we can deal with it and these are the people who can talk about it.”

0:36:30.7 RG: I saw this with the ADOS movement. Well, actually, your listeners might not know much about that, but we certainly saw it with the Black Lives Matter movement.

0:36:40.8 SC: Right, okay.

0:36:41.1 RG: Right. So yeah, that would be probably the prime example, where it started, I believe, on Facebook, and then people were talking about issues with police brutality there, and then it migrates to Facebook. And it’s not just saying Black folk are being harassed by police or being shot more. It’s also having the examples. It’s also understanding how people will respond to that and developing ideas that way. And so through that back and forth, you end up getting this general idea that became quite important in American society.

0:37:18.0 SC: So now it’s my turn to be slightly contrarian, just for purposes of asking questions. Is the contrary worry that it leads to splintering of the community or the nation or whatever, that people go into their own little groups and their own little identities and lose some commonality?

0:37:37.4 RG: Yeah, that is a concern. I’ll give you the standard critical theory response. Critical theory is quite a buzz word these days.

0:37:50.6 SC: [chuckle] It is.

0:37:50.8 RG: But this is the standard response. And the response would be that those groups are already marginalized, and so you maybe, as a White male or someone who has access to things, you may see this now as being divisive, but before, those groups were already divided out, if I may think of it that way. And so this is just them now arguing for inclusion in the national narrative. I’m not saying that’s accurate or not, that’s more of a theoretical way of thinking about it, but that would be, I guess, the response from a lot of folks.

0:38:27.1 SC: I think that makes sense. A lot of what gets passed off as unity and agreement is actually just silencing the people who would disagree, and maybe social media makes that harder to do.

0:38:39.8 RG: Yeah, that’s possible. Yes, that’s true. Actually, so let me double-back a little bit since we’re talking about it. A lot of folks are concerned about this cancel culture, and not the culture we were talking about of the students on campus, but just online. Someone wants to develop a counter-narrative to this anti-racist thing, or they have a different take on how we should talk about trans persons, they are not able to say that. So it might be that those marginalized groups have now… They have a symbolic weight and a moral weight which now makes them a part of the national narrative, but now they may be silencing different voices on their own, right? I don’t know.

0:39:32.1 SC: Yeah, I think that this is… We can talk about this more because, again, I don’t have very fixed views about it and would love to learn more. Clearly, there’s a couple of examples just last week where people who I thought pretty highly of were fired from their jobs for saying completely innocuous things on Twitter, and I think that’s a real phenomenon that happens. On the other hand, I’m reluctant to label it as a culture, and I think that’s sort of a lazy shortcut to silence people who are trying to critique bad things. So even Will Wilkinson, who was a previous Mindscape guest… I don’t know if you followed his story. Did you follow his story by the way?

0:40:14.3 RG: No, I didn’t.

0:40:15.0 SC: So Will Wilkinson is a sort of Libertarian think tank guy, relatively middle of the road, and he was making fun of the Capitol insurrection by putting a bad joke on Twitter where he said, “Maybe Biden could unite the country by lynching Mike Pence,” since the MAGA protesters wanted to do that, some of them anyway. Now, this might be very well characterized as a joke in bad taste, but he got fired from his job at the think tank for that Twitter joke that he apologized for. And to his credit, he then wrote a long article saying, “Yes, I got fired, this is bad, I think it’s silly, but it’s not cancel culture. It’s lazy and reductive to call it cancel culture. We should think about these things on a case-by-case basis.” So I’m a little skeptical of the idea that there’s a whole culture out there of doing it, rather than just the eternal human tendency to occasionally overreact and cover your ass in bad situations.

0:41:19.1 RG: That might be it. It could be that as as human beings we are wired to sort of connect with others and then enforce our group’s norms, I guess. And if we see something out of the norm, we’ll say something about it. But this is 2020, 2021 now, and so instead of just saying, “Oh, Laura hadn’t cut her grass,” and then just complain to the neighbors, you can now do that online and a million people can then join in, and then all of a sudden your employer has to, for damage control, has to fire you. So it might just be a combination of technology and human nature, you’re right.

0:42:00.7 SC: And I think that is a danger when you can sort of amplify these petty grievances into getting people fired using social media, but on the other hand, I don’t wanna shut out criticism of people when they say bad things. So it’s tough to be a critic of cancel culture and also a free speech absolutist, even though those groups tend to often overlap in a big way. But anyway, good, neither one of us has the complete and final answer to that, I think we can admit those questions. But you mentioned this phrase “critical theory,” which is another one which, like you said, has become a hot button issue, and I’m not exactly sure why. I was an undergraduate in the ’80s and then a graduate student in the ’90s, and I had friends and I took classes where people talked about deconstruction and the Frankfurt School and critical theory, and then it just disappeared, I never heard about it. And suddenly this year, it’s all over the place. The administration is making proclamations about it. So what is critical theory, and how did that happen?

0:43:03.0 RG: I don’t know how it happened either, [chuckle] but I can kinda give a broad overview of what critical theory is. So it’s a branch or maybe a viewpoint within social sciences that starts with some assumptions, that there is inequality in the world and it’s due to oppression. So we know there’s inequality, it’s just a demonstrated fact. And so they’re assuming that it is because of some type of… Forms of oppression. Now we’re talking about racism, but it doesn’t have to be. It could be sexism, it could be heteronormativity, it doesn’t matter. And so the critical theorist, their task is to try and understand the structures in place in society that produce and reproduce that oppression and then dismantle those structures. And so for a lot of folks, that’s scary, because if you’re happy with your life or even if you’re not entirely happy, but you think that, okay, things like… And I should back up a little bit and say that some of the things that a critical theorist would say is causing this oppression is a focus on objectivity and meritocracy, on objective science even. So not just objective facts, but this idea that you can create some kind of knowledge based on just objectivity.

0:44:35.2 RG: These ideas are… Individualism even, liberalism. So they want to critique those ideas to the extent that they are reproducing inequalities and oppression. And so that, for a lot of folks, can be a little troubling. If you believe, as most people do, including myself, that, “Look, there is an objective reality out there, that individualism is a lot better than collectivism.” Now, you have these ideas and then you hear someone comes along and they say, “No, these things are bad, and they’re actually creating… They’re the cause of racial inequality in society, and we have to do something about it.” That’s gonna be a problem for a lot of people.

0:45:26.3 SC: Yeah, and it’s definitely one of the examples where a slightly nuanced take is almost necessary, right? Because I believe in the real world, I believe in objective reality, and I would strongly argue against anyone who thought that a conviction that the objective real world exists is somehow the tool of the oppressor. But I am sympathetic to the idea that the rhetoric of objectivity and meritocracy, etcetera, can be used to paper over oppression and discrimination. Right? So it’s exactly one of these hot button issues where it’s just hard to have that careful conversation ’cause everyone wants to pick out the worst of what the other side is saying and then highlight that and forget about everything in between.

0:46:10.9 RG: That’s right, that’s right. And from that broad overview, I guess… I mean it’s obviously more nuanced than that, but that’s what I can think of. Did we say we were gonna talk about CRT? ‘Cause a lot of times people want me to be that person, to talk about CRT. They can’t seem to get critical… So I said, CT is critical theory, and then a branch of that is critical race theory. So often I’m asked to talk about these things because they can’t get in someone to talk about it. But in any case…

0:46:39.9 SC: You brought it up. I didn’t even think of it.

0:46:40.0 RG: So it’s in my head a lot. But what often happens is it gets distilled into these sort of terms that have some, I guess, prima facie validity, and it’s like a validity sandwich. So, if you give the broad idea, so let’s say white fragility, there is some validity in it. And then if you start talking about it, people are gonna say, “Wait a minute, this is not falsifiable, this is not scientific, this is just divisive.” And then they will be right. And then when you sit in a class and you learn about it and you realize, “Okay, I know it makes sense.” It’s that kind of sandwich that’s a problem.

0:47:23.6 RG: So I’m sure you’ve heard of white fragility, this idea that if you try and talk about race, white folks go bonkers, this type of thing, propagated by Robin DiAngelo. Okay, and this is definitely a critical theorist idea. It’s like, “Okay, white folks have been born into a society that has inculcated these racialized views in them, and so they need to be aware of that, and we need to be aware of that and critique those things, and one way is to be aware of your fragility.” I don’t know how useful that is, I’ve had some guests on my show to talk about it, but that’s sort of emblematic of this approach.

0:48:04.6 SC: Yeah. And how does that relate to the very common move that is made that, “To make real progress, we should be focusing on economics and class, and talking about identity or race or gender is a distraction from those real questions”?

0:48:22.6 RG: Well, me personally, I think that there are class-based issues and then there are race-based issues. And on a practical level, we are a society that has to negotiate things. So if people are more willing to support a class-based policy, just dealing with poverty in the United States, to make it more clear, then okay, because it will, of course, also benefit people of color. But if you wanna really aim the bullseye at a problem, then you have to deal with the issue that underlies it, and so some of those things are exclusively race-based issues.

0:49:07.0 SC: So you think of yourself as more or less a pluralist along the dimensions that are worth being critical about, that we should explore all of these different ways in which things could be less than ideal in society?

0:49:21.0 RG: Well, I think if… I don’t know what you mean. So you mean as a critical… Like a critical scholar and critique things? Or you mean just…

0:49:31.7 SC: I guess I think that… And maybe this is an incorrect impression on my part, but there seem to be some people who are just reductive about what is bad about society and how to fix it. “If we could just make everyone have an equal income, everything would be fine. Or if we could just get rid of racism everything would be fine.” And it sounds like you’re more open to saying, “Well, no, there’s all these problems, and they’re a little bit different and we should think about all of them.”

0:50:00.6 RG: Oh, that’s absolutely true. Every phenomenon in society is multi-causal. It’s always gonna be the case that there are several things involved, and so we just sort of select the three or four variables that explain the most variation, I guess, and go with them. And so income and wealth are two of the main ones, and so that would be a way to go. I think that when it comes to policing, Black communities are over-policed and there are some ripple effects from that, that comes from just the over-policing. And so if we can handle that, that would be a good way to go. So, absolutely.

0:50:43.6 SC: And can we say at the level of data that if Black communities are over-policed, etcetera, it is not something that goes away if we control for poverty or income or whatever, it’s not just the poor communities are over-policed and Black communities are often poor, it’s really a separate thing, that Black communities have this problem?

0:51:04.5 RG: It’s two things. I think that if we would control for class we would still see that Black folk… In fact, I’m sure of it, that we’ll see that Black communities are policed more. But I am not sure if that’s even the best analogy, or the best way of thinking about it, because it might be that someone could argue, I think accurately, that the reason that they are policed more is because there’s more crime there. So there’s more crime there at time one, and then they’re over-policed at time two.

0:51:40.0 RG: So I’m not entirely sure if controlling for class is that helpful. I think instead what we would have to do is look at the ways that they’re policed, realizing that poverty does indeed create crime, but instead of having an overly punitive approach in those areas, come up with alternative ways to deal with juvenile delinquency, to deal with these low-level drug offenses that really you’re putting people in jail for years and years and years for these minor offenses. And even the relationships between police and citizens, that might have to be considered. The classic comparison that I’m sure you’ve heard is that, “Okay, if you look at… ” There’s a study done about Oakland, and we know that there’s more drug use in the White side of Oakland, I guess. I say “we know”, I didn’t know, but I read this research that…

0:52:46.1 SC: “It is known”

0:52:47.0 RG: That there’s more drug use there, but somehow the police are all all in the Black side of town and they end up arresting more people for drugs. Well, that’s kind of a… You can sort of say, “Well, that’s a class issue”, but I’m not entirely sure. I think it’s more that those police have been there for decades, there’s this sort of understanding that, “Okay, this is where the crime is.” And there is more violent crime in those areas, and so they end up going into those areas. And maybe they’re dealing with the violent crime, but they’re also sopping up a lot of other deviance that really should just be left alone. And those people then get in the system, and then you got this ripple effect where they don’t finish high school, they start to drop out of society, and then they don’t get good jobs, they don’t start strong families, all this down the line.

0:53:38.9 SC: This is why the cause and effect analysis is so extraordinarily difficult in sociology or economics, and it’s just much easier to become a physicist, frankly.

[laughter]

0:53:51.0 SC: How do you feel…

0:53:51.9 RG: Yeah, I… I’m sorry, go ahead, no.

0:53:53.8 SC: I was gonna ask, how do you feel about the claim that one is either racist or anti-racist and there’s no in-between? Which that’s another hot button thing that people have been arguing about recently on the social media.

0:54:08.0 RG: Yes, yes they have. So if I understand it correctly now… And I listened to his… You’re talking about Ibram Kendi’s book?

0:54:17.5 SC: Yeah.

0:54:18.3 RG: And I listened to his book, How To Be An Antiracist. I thought it was kind of interesting. We grew up at almost the same time, and so he speaks about some of the things that I experienced. But the way I understand it now is that, given a policy or an idea, that idea can either reproduce an understanding that races are different or it can eliminate or mitigate the notion that races are different, given an idea. And then a policy that’s about race can either reproduce racial inequality or reduce it. I think that’s how it works. And it’s a very… On the one hand it’s very simple, because people can say, “What do you mean? Can I just be ‘not racist’?” Right? And that seems very logical to me.

0:55:12.0 RG: But on the other hand, aren’t there other things in nature that it’s either… Like it’s not static, like it’s either moving forward or back or producing energy or not? I don’t know. I’ve seen him explain it, or listened to him explain it that way, that it’s just not binary. When you do something about… When you vote on a racial policy, or a policy that has racial implications, you’re either gonna vote to reproduce that inequality or mitigate it.

0:55:45.0 RG: So I don’t know, man. [chuckle] I don’t know. It is quite a hot button thing. I guess I’m in favor of saying that it’s important to have more nuance, even if you have that one dimension of racist and non-racist, maybe you can have some kind of cross-cutting dimension where there’s another value that matters. So, okay, you might be voting for this policy that’s racist in its implications, so maybe you’re voting for voter ID laws or something. And you know that it’s going to impact people of color more. Kendi would say that, “Okay, that’s a racist policy, you’re being racist,” on that dimension. But then there could be another dimension where it’s like, “Well, I’m voting for safety or something, and I’m being for safety or pro-safety, there’s no in-between.” [chuckle] And so you have another dimension. And so nuance can be added to this discussion in that way, I believe.

0:56:51.0 SC: So, yeah, this is a very typical academic move to complicate your model by adding more variables to fit all the different possibilities, but I’m in favor of it. I’m a typical academic, I like it. Which I think leads us to… Okay, so I think that given everything that you’ve said, it’s fair to classify your views, correct me if I’m wrong, as progressive on social issues, in favor of social justice, etcetera, but then you have this interesting wrinkle where some of your attitudes could be described as socially conservative. And I think that… And as you point out, and this is completely compatible with other things I’ve read, that’s not so uncommon in African-American and other minority communities. So is that an accurate way of putting it, and how would you sort of elaborate on that?

0:57:39.0 RG: Yes, that’s accurate. I think most Black Americans, especially working-class and in poverty, are socially conservative. Even middle class, actually. So just Black Americans in general are socially conservative but economically progressive. And our social conservatism, if I can sort of indicate that by some kind of policies maybe, when it comes to things like abortion, we are more likely to say pro-life. And before I get cancelled, I’m gonna explain what’s going on here. So let me… But let me go through this first, right?

0:58:20.9 SC: Okay, I wasn’t gonna cancel you, Rod. Don’t worry.

0:58:25.0 RG: So we would be more pro-life. When it comes to immigration, we’re more parochial. We’re more interested in what’s going on in our neighborhoods. I’m saying “our”, I gotta give the caveat always that this is just kind of my interpretation from personal experiences and looking at some survey data that anyone can get from Pew Research, it’s kind of clear these things. When it comes to gay rights, famously, Black Americans had to be pulled along for gay rights with the Democratic Party. Prayer in schools, even things like corporal punishment. So I would say… And just… Yeah, so these ideas are really socially conservative ideas, and although at this point in my life I’ve kind of left that environment, I still kinda carry them with me. But the way that this is often experienced within Black America is a personal choice.

0:59:26.1 RG: It’s never the case that we would sort of wanna start a grassroots organization for pro-choice or start a… It’s just something like, “Okay, you know what? If that person over there wants to be… They don’t want prayer in schools or they don’t ask their kids to pray, fine, that’s their choice. But this is what I wanna do.” And so I think that is very common within Black America, even for academics who are moving away from that. I’m not necessarily very religious, I know that you’re an atheist, I’m not very religious, but I would call myself a cultural Christian. But the thing is the economic aspects of life are so important until… Those socially conservative things are nice, but we could handle that in our own home, and so we end up voting Democrat because of things like Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society and other Democrats since then focusing on racial issues, even if they’re just identity and not always helping us economically, but at least they recognize that, “Look, race is a central issue in our lives.”

1:00:40.9 SC: Right. It’s a bit of an aside, but let me ask you, do you know Anthony Pinn? Tony Pinn at Rice University?

1:00:47.5 RG: I don’t, no.

1:00:48.1 SC: He was one of the very first guests on Mindscape, I think he was episode three or four. And he’s African-American, he grew up a child preacher, became an atheist and is now an atheist theologian at Rice, who is really, really interested in this idea of why more Black people aren’t atheists. And he says it’s obvious why, because the church is really useful to their lives and their communities in a way that atheism just isn’t, and it’s just not about arguments at the philosophical level for or against the existence of God. And I wonder how that ties into this bigger picture of… He would be a great guest for your YouTube channel, by the way. But I wonder how this ties into this bigger question of cultural conservatism versus economic progressivism. Is it true that sort of both of those attitudes are responses, or at least compatible with, being disadvantaged minorities? That you want to have a strong family, you wanna stick together, and you also want the economic goods to be distributed more widely?

1:01:58.5 RG: Oh, that’s true. That’s absolutely true. It’s cross-racial, actually. So you’ll have a lot of working-class and poor White Americans who also have similar attitudes like this. And I think Dr. Pinn… You said Tony Pinn?

1:02:11.8 SC: Yeah.

1:02:12.0 RG: Is correct, that it’s functional. It’s a way of providing meaning for your lives and a sense of purpose, which we all need. I always wonder how atheists… What is the substitute for that thing that I think we’ve evolved to have, this meaning and purpose? But yeah, absolutely. It is a response to economic insecurity and poverty. I think that from a sociological angle, I can say that… And maybe you had someone else on to talk about the positive impacts of religion, and I’m not talking about the truth of it, I’m talking about just what it means for social outcomes, and it seems as if people who have some kind of faith, they tend to have more positive social outcomes in terms of income, education, crime, overall happiness, marital stability. So there’s something going on in there that I’m not qualified to talk about, but there’s something happening.

1:03:17.5 SC: Yeah, no, Tony Pinn’s formulation is that atheism fails to provide a soft landing for communities that sort of need that social cohesion that religion tends to offer. And I wonder if it’s even… I recently had Joe Henrich on the podcast, who’s a Harvard anthropologist-psychologist who talks about WEIRD societies, western-educated, industrialized, rich and democratic. And one of the things that we almost… It’s interesting, because our literal psychology and brain physiology is affected by these cultural norms that we grow up in. And the Enlightenment and its emphasis on individuality and every person for themselves is a way of living and being in some sense, a value system, but it’s not the only one. And there is an alternative that says that, “No, I should sacrifice a bit of my individuality to a bigger unit,” whether it’s a family or a culture or a nation or something like that. And I don’t think there’s an obviously right or wrong choice here, and I wonder how that… That is a vague question, but I wonder how that plays into what you’re thinking about here.

1:04:31.8 RG: Well, I don’t know. Just personally here, this is not anything that I know in any academic sense, but I feel like a sense of belonging in a… The group provides a sense of belonging and meaning that you cannot generate on your own. So this isn’t about religion specifically, but it’s just about groups in general. And so you mentioned the Enlightenment and individualism, and I think since maybe the ’60s or ’70s we’ve kind of ramped that up even more. So the Enlightenment may be a sort of ideological or idea-based individualism, like we should think as an individual, but I think we now live materially as individuals, and that’s a problem. We live in these homes with… We feel that we have to get married and go off and have two kids, move 50 miles from your parents and a live alone in a house, and that means that we’re doing a good job and we’re happy. But I don’t think we are. I think there have been so many studies showing that once your material needs are taken care of… So we’re in a wealthy society, even the poor tend to have their basic needs met most of the time.

1:05:48.4 RG: So once you get that level of material comfort, then what actually makes you happy is other people. And I don’t think we push that enough. We focus more on, “Okay, go out and have a nice career,” and all that stuff. And I’m not entirely sure that’s the right way.

1:06:04.3 SC: No, actually I’m very much on your side when it comes to that but it’s, again, it’s one of these really hard problems, because I am very much in favor of the right or the ability of people to pick their jobs, pick their homes and their locations, and even pick their friends. But I think I would agree with what you’re implying, that as a society, we haven’t constructed institutions that make it easy to find the right groups of people who we want to hang out with in formal or informal ways. Maybe… Is this a place where techno-optimism can be raised again? And can social media and the Internet and so forth, even if not now, can they someday help people find their groups?

1:06:51.0 RG: You know what? I think so. I think that as we… So if you are talking with a healthcare professional and they’ve got these online medical consultations now… And I’ve never been to a therapist like that, but they now do it online. And from what I understand, the face-to-face matters. But even online teaching, the face-to face matters because we’re sort of wired to take cues from other people. And so I can imagine a Twitter that’s not all text and GIFs and short two-minute videos, but it’s actually people who are sharing a room together, and maybe it’s a permanently online room or something, and so it’s just open on your Amazon Echo or something, and then you can sit down and tweet a conversation. And then, you know… I don’t know how this would work, I’m just kind of spitballing here, but the point is that we could get to that point where we can simulate an actual connection and not this sort of digitized fake one, and it might tap into what we have evolved to expect from another human being.

1:08:06.9 SC: Yeah, I haven’t thought about this very deeply, but that sounds right to me, and it sounds like something that we don’t do very effectively, but we could. This might be a future way of going. I tend to suspect that, as we were talking about the usefulness of Black Twitter before, I tend to suspect that this kind of ability of social media or the Internet more broadly to connect people is especially valuable for people who find themselves in tiny, tiny minorities where they wouldn’t run into each other. That’s the downside of the… What I would call the downside of the sort of culturally conservative vision of everyone has their families and their communities and so forth, that if you just don’t fit in, that can be a really tough situation to find yourself in.

1:08:52.6 RG: Oh yes, absolutely, absolutely. With some psychological effects. If I can bring it back to the race issue a bit, we find that middle class Black Americans who are in White spaces are suffering some impacts of racism. I think the Harvard psychologist David Williams talks about this, he would be an interesting guest, if he would do it. He does this research where he looks at the high blood pressure, how high blood pressure for Black Americans raises or increases when they’re in White spaces, and how this then leads to other negative consequences down the line.

1:09:31.8 SC: Oh that’s very interesting.

1:09:32.0 RG: And it’s because they’re in spaces where they don’t have anyone that they feel they can connect with, and so they die sooner. I think his TED Talk was he charted a class from Harvard that graduated in 1985 or something like that, and he looked at… Or I guess earlier than that, because the people had started dying. And he said, “Wow, this is amazing.” You’ve got the same income, as far as he can tell the health behaviors were similar, but all of a sudden you’ve got Black folk dying 10 years sooner than White. And so he makes the hypothesis that it’s because of racism raising high blood pressure.

1:10:13.6 SC: That is very interesting, and it seems plausible to me. I mean, I haven’t seen the research. The thing that I am familiar with that sounds very similar to that is a long time ago I would have said that the idea of single-sex schools for girls and boys, secondary schools or elementary schools, sounds terrible. You’re taking people away, kids away, from socializing with other kinds of people, etcetera. But then there are studies, you have to listen to the data, right? There are studies that, especially in Math and Science, girls who take math and science classes only with other girls do better and come out of them better and more self-assured and more confident than ones that are in co-educational environments, ’cause then the boys just sort of get all the attention and shout them down, is the slick, maybe accurate, explanation. I don’t know.

1:11:03.0 SC: So yeah, so I do think that this is one of those aspects which maybe people who are skeptical of social justice initiatives would tend to downplay these sort of difficult to quantify but very much there influence you have that is not… It’s not like you’re facing white supremacists or misogynists or whatever, but there’s this sort of atmosphere around you that can just wear you down and cause deleterious effects down the line.

1:11:32.5 RG: Yeah, yeah, that makes sense.

1:11:35.0 SC: And so I wanna go back to… I don’t wanna quite give up the conversation about the cultural conservative, culturally Christian attitude because, like you say, this is not just you, this is quite common among African-Americans. Can we make it a little bit sharper in terms of what it means in terms of policies and things like that? So you say that you’re not in favor, even though you’re pro-life personally, you’re not in favor of restricting abortion at the legal level. Are there political decisions that you go opposite to elite progressive activists because of your cultural conservatism?

1:12:13.4 RG: I would. I can see how faith-based programs could help Black America, especially in working-class communities, maybe for the same reason that the guests that you had on talked about. I think that they are… The benefits are that they provide cohesion, and we know that social cohesion tends to reduce crime, and that is very important. I mean, crime overall has gone down, so in some ways this analysis is getting kind of old. But certainly in the late ’90s, early 2000s, that was a really big issue, like these petty street crimes in Black neighborhoods. And so the idea would be that if you had more strong community institutions where young people, but also people of age, could meet and communicate and get to know each other, that cohesion would reduce deviance. So any kind of policy that deals with that, or makes funding available for faith-based institutions. And really we’re talking about churches here. But it can also be… We have a lot of Black Muslims. But yeah, faith-based organizations, I would certainly support that, I think that would be a good idea.

1:13:33.1 SC: And what is the current status of things like that? I remember back in the George W. Bush administration, that was the hot topic, hot button issue, at the time, ’cause they were definitely pushing faith-based initiatives, but I’m not quite sure what has happened to that initiative.

1:13:48.0 RG: Dead in the water.

1:13:49.0 SC: Yeah, okay. So if I try to put words into your mouth, and then you can correct me, the First Amendment says we shouldn’t have government establish a religion, or Congress should not establish a religion, and presumably were in favor of that, but maybe there’s space for working with religious institutions in communities where that would be a benefit. Is that the idea?

1:14:11.6 RG: Absolutely, ’cause you already have those norms in place. I could even imagine… So, I don’t know how this works, but… I don’t know if Catholic churches get… Or Catholic schools get any funding from the government. I assume the universities do, I don’t know about grade school or whatnot. But I can imagine that you may have a church that says, “Okay, we wanna offer some type of… We wanna start a charter school or something, and we wanna do it along these particular principles, faith-based principles or something.” Well, that’s already gonna be a draw for the parents, and it’s not as if they’re gonna… Just because they are offering faith-based teaching, that they’re gonna be better at teaching, but it might attract Black Americans more. And that institution is already there, and so that might work that way. But back when George Bush was doing this, I wasn’t a political animal back then, so I don’t know the details of those things.

1:15:22.1 SC: A lot of times I worry about labeling certain things as religious or faith-based if maybe there would be a better label along the lines of principle-based or morality-based institutions.

1:15:41.8 RG: Oh, that’s interesting.

1:15:43.0 SC: I think when we talk about faith-based exceptions to certain laws or regulations, as an atheist that seems a little bit unfair. What if I have a really strong moral objection to something but my morals are based on something that is just naturalist rather than theistic? I’m being discriminated against, I’m being oppressed, but I’m not sure how to actually make it work in practice. I don’t know if you have any ideas.

1:16:10.6 RG: I don’t, but the re-framing of it is great. Yes, that makes sense to me.

1:16:15.5 SC: Yeah, something to think about.

1:16:16.0 RG: A morality-based institution or policy or initiative, certainly. Of course people would then say, “Well, what do you mean morality? Is your morality my morality?”

1:16:24.4 SC: Exactly.

1:16:25.9 RG: But yeah, I still get what you’re saying.

1:16:28.7 SC: I mean, do you think that there is a substantial disconnect between what we might call progressive activists who think of themselves as fighting for the rights of Black people and trans people and whatever, and the actual people who might have different sets of values? Is that a big potential cause of friction within a coalition that should be working to the same goals?

1:16:56.0 RG: There is a disconnect, but I don’t detect any friction yet. It’s the same disconnect that you’d get in any type of situation where you’ve got the idea generators who may not necessarily be in that situation but they’re sympathetic to it, and so they come up with these ideas and they’re in a think tank or they’re at a university or something, or they’re in an ivory tower, and they come up with ideas that are consonant, or I would say maybe even parallel to what people in working-class environments think, but they don’t always converge. A classic example would be the “Latinx” word. So the idea that, okay… And I hope this is right, that Hispanic is including Spain, and if you’re from Latin America then why do you wanna be included with people who colonized you? Or something of that nature. And so we wanna use this term Latinx. Now, working-class Latinx people, Hispanic people…

[chuckle]

1:18:06.9 SC: Latino and Latina, yeah.

1:18:07.0 RG: Don’t necessarily care about that that much, but the general idea of respecting their culture and understanding that that probably Spain committed a lot of atrocities in colonizing that land, they agree with, right?

1:18:23.0 SC: Right.

1:18:23.1 RG: So that happens quite a bit. Even this “defunding the police” idea. So, working-class Black Americans, they do not want the police out of their neighborhoods. I don’t even think they really want them defunded. But the general idea that police tend to be overaggressive in ways that you can’t always measure. So the interaction between a White police officer and a Black male is probably gonna be more fraught, is more fraught, including words that indicate how fraught that situation is, as opposed to a White police officer and a White female.

1:19:09.0 RG: There have been so many studies and surveys and just anecdotal evidence saying that, “Look… ” And comics, actually. I think Dave Chappelle does this wonderful routine, where White folks generally have a more positive view of police, and that’s historical and it repeats over and over again. So I’m saying that because Black Americans in working-class neighborhoods have a somewhat antagonistic relationship with police. They would like police reform. At the same time, they don’t want defunding, because they want the police there. So it’s one of those things where there’s parallel interests, but they don’t always converge.

1:19:52.0 SC: Yeah, exactly, and I think that is… Maybe it’s just inevitable, maybe that’s just part of the game and there will always be little tiny frictions because different subgroups will move in different directions at different rates, but as long as we all move in the same ultimate direction, it’s okay. So I guess I don’t have a final question, but let me… I’ll sort of say something as a final thought and maybe try to get your version of it or your response to it.

1:20:18.1 SC: A lot of these… When we think about activists trying to push inclusive language like “Latinx” or radical ideas like defunding the police, part of me says, “Well, I don’t necessarily agree, maybe I do, but maybe I don’t agree with that specific recommendation, but their heart’s in the right place. They’re trying to make the world a better place. They’re trying to fight for something good.” And to me, that counts for a lot. I will respond differently to that, even if I disagree with it, than I will to someone who I think is dismissing racism as a problem, where I think that not only do I disagree with them but their heart is not in the right place. And this goes back to where we started in terms of communicating with people on the Internet and choosing who to engage with and all that. I mean, maybe we can close with you talking a little bit about your philosophy, and especially ’cause I always like to close on an optimistic note, so I like the fact that you’re an optimist about these things. The attitude we should take towards people we disagree with, ideas we should disagree with. Do you have a way of negotiating those tricky waters?

1:21:27.9 RG: Well, when I communicate with people, I don’t always believe that I’m gonna change their minds. But I don’t know if that should be the goal, really. I think when you communicate with people, the idea is, or the goal is, to understand the idea that they are communicating with more nuance, and then to humanize the person that you’re communicating with, ’cause it’s often the case that… You gave the example of the person who might say racism doesn’t exist, and maybe they’re being disingenuous or they’re just not communicating in good faith. But if you talk to them long enough, most of those people, they do have some idea, they have some understanding of why that’s the case.

1:22:18.5 RG: So, okay, just to say 50% of those folks, they’re probably just bad faith, but a lot of people don’t think that racism matters, ’cause they’re navigating their everyday lives and the data that they’re taking in leads to this conclusion that, “What are you talking about? I have no antipathy in my heart, everything’s fine, my neighbor’s Black. I mean, come on, this is okay.” And so when you talk to them more, even if you think they might be wrong about certain things, you see why they come to their views, and so that kind of nuances their idea, and it also humanizes them. And I mean, come one, this is a democracy here, you should not expect people to just follow along with what you say. You try and communicate and hopefully we can negotiate a path for moving forward.

1:23:09.4 SC: I think that’s fantastic. I think that’s a very good way of putting it, especially the idea that the purpose of talking to people is not simply to change their minds. Sometimes you wanna listen to people you disagree with just to understand them better and maybe have them understand you, even if no one’s mind changes at all. That’s still… That’s a goal maybe we forget these days. And so, hopefully, this little conversation we’ve had put some ideas into people’s minds, whether it changes them or not, but I think it was a lot of fun. So, Rod Graham, thanks very much for appearing on the Mindscape Podcast.

1:23:42.2 RG: Thank you.

[music][/accordion-item][/accordion]

Loved this one. For obvious reasons, reporters and laypeople discussing sociological topics are even more confident about their personal opinions than even cosmological physics, Everett-ians, etc. Very refreshing to hear a professional sociological perspective on the dominant forum for community, 2021. Extremes on liberal topics so often feels like semantic ‘wrangling’, and communicating only through an open universal town square, exposed to the world, our new reality, quite frustrating for me. Very thoughtful and articulate and informative topic. Our commonwealth, our language, our culture have all changed more in the past 5 yrs than the past 70. Thanks.

Pingback: Sean Carroll's Mindscape Podcast: Roderick Graham on Cyberspace, Race, and Cultural Conservatism | 3 Quarks Daily