It has often been said, including by me, that one of the most intriguing aspects of dark matter is that provides us with the best current evidence for physics beyond the Core Theory (general relativity plus the Standard Model of particle physics). The basis of that claim is that we have good evidence from at least two fronts — Big Bang nucleosynthesis, and perturbations in the cosmic microwave background — that the total density of matter in the universe is much greater than the density of “ordinary” matter like we find in the Standard Model.

There is one important loophole to this idea. The Core Theory includes not only the Standard Model, but also gravity. Gravitons themselves can’t be the dark matter — they’re massless particles, moving at the speed of light, while we know from its effects on galaxies that dark matter is “cold” (moving slowly compared to light). But there are massive, slowly-moving objects that are made of “pure gravity,” namely black holes. Could black holes be the dark matter?

It depends. The constraints from nucleosynthesis, for example, imply that the dark matter was not made of ordinary particles by the time the universe was a minute old. So you can’t have a universe with just regular matter and then form black-hole-dark-matter in the conventional ways (like collapsing stars) at late times. What you can do is imagine that the black holes were there from almost the start — that they’re primordial. Having primordial black holes isn’t the most natural thing in the world, but there are ways to make it happen, such as having very strong density perturbations at relatively small length scales (as opposed to the very weak density perturbations we see at universe-sized scales).

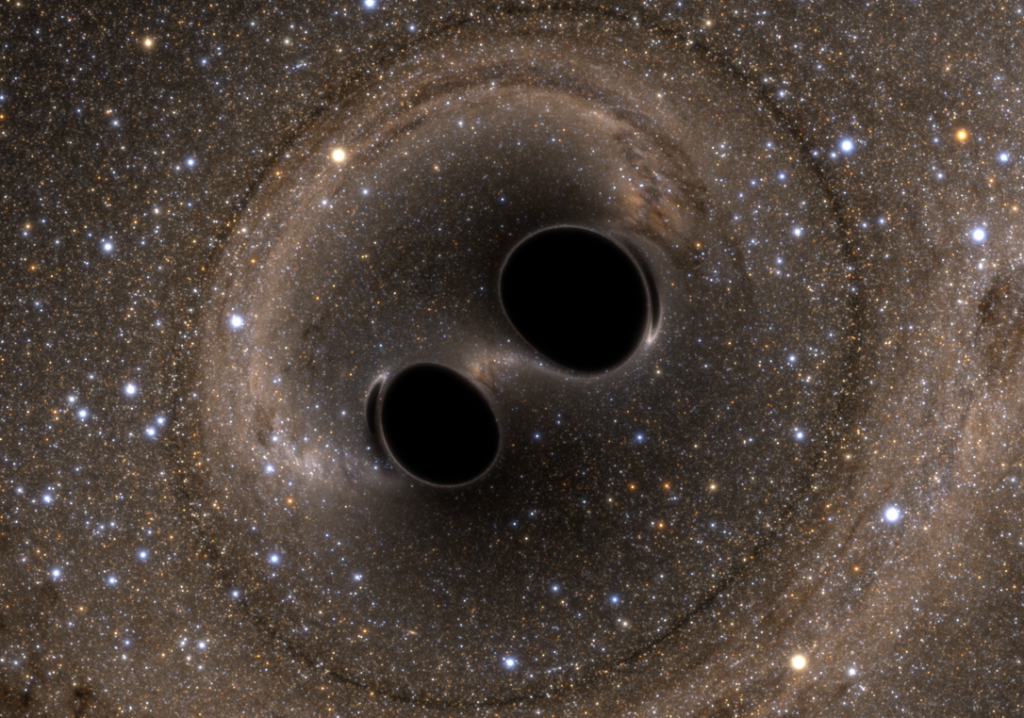

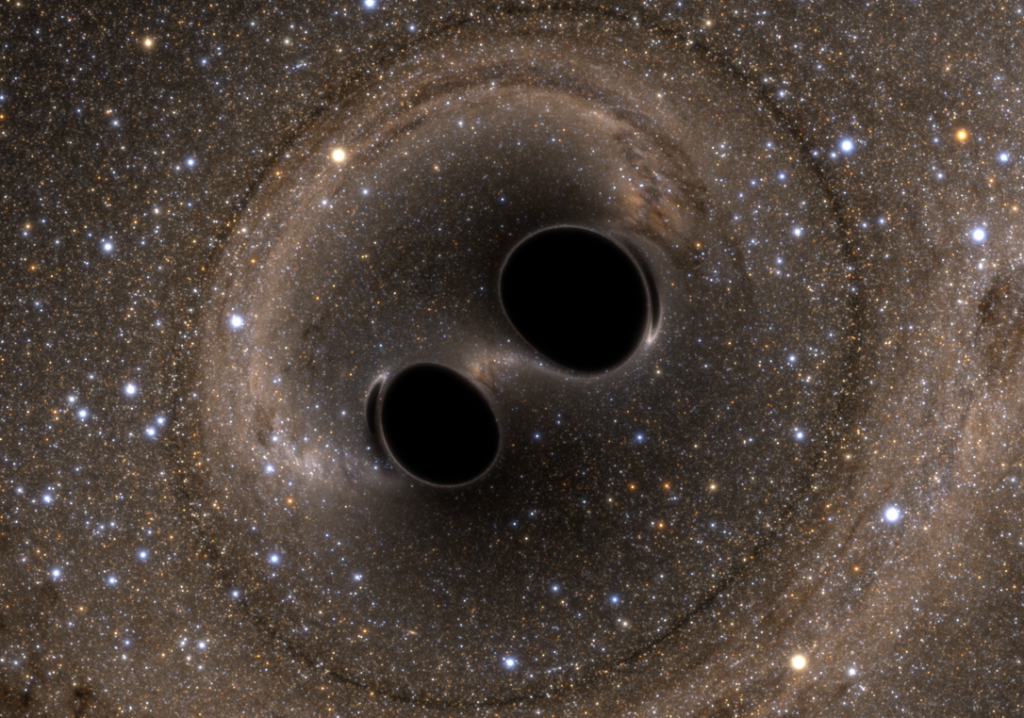

Recently, of course, black holes were in the news, when LIGO detected gravitational waves from the inspiral of two black holes of approximately 30 solar masses each. This raises an interesting question, at least if you’re clever enough to put the pieces together: could the dark matter be made of primordial black holes of around 30 solar masses, and could two of them have come together to produce the LIGO signal? (So the question is not, “Are the black holes made of dark matter?”, it’s “Is the dark matter made of black holes?”)

This idea has just been examined in a new paper by Bird et al.:

Did LIGO detect dark matter?

Simeon Bird, Ilias Cholis, Julian B. Muñoz, Yacine Ali-Haïmoud, Marc Kamionkowski, Ely D. Kovetz, Alvise Raccanelli, Adam G. Riess

We consider the possibility that the black-hole (BH) binary detected by LIGO may be a signature of dark matter. Interestingly enough, there remains a window for masses 10M⊙≲Mbh≲100M⊙ where primordial black holes (PBHs) may constitute the dark matter. If two BHs in a galactic halo pass sufficiently close, they can radiate enough energy in gravitational waves to become gravitationally bound. The bound BHs will then rapidly spiral inward due to emission of gravitational radiation and ultimately merge. Uncertainties in the rate for such events arise from our imprecise knowledge of the phase-space structure of galactic halos on the smallest scales. Still, reasonable estimates span a range that overlaps the 2−53 Gpc−3 yr−1 rate estimated from GW150914, thus raising the possibility that LIGO has detected PBH dark matter. PBH mergers are likely to be distributed spatially more like dark matter than luminous matter and have no optical nor neutrino counterparts. They may be distinguished from mergers of BHs from more traditional astrophysical sources through the observed mass spectrum, their high ellipticities, or their stochastic gravitational wave background. Next generation experiments will be invaluable in performing these tests.

Given this intriguing idea, there are a couple of things you can do. First, of course, you’d like to check that it’s not ruled out by some other data. This turns out to be a very interesting question, as there are good limits on what masses are allowed for primordial-black-hole dark matter, from things like gravitational microlensing and the fact that sufficiently massive objects would disrupt the orbits of wide binary stars. The authors claim (and quote papers to the effect) that 30 solar masses fits snugly inside the range of values that are not ruled out by the data.

The other thing you’d like to do is figure out how many mergers like the one LIGO saw should be expected under such a scenario. Remember, LIGO seemed to get lucky by seeing such a big beautiful event right out of the gate — the thought was that most detectable signals would be from relatively puny neutron-star/neutron-star mergers, not ones from such gloriously massive black holes.

The expected rate of such mergers, under the assumption that the dark matter is made of such big black holes, isn’t easy to estimate, but the authors do their best and come up with a figure of about 5 mergers per cubic gigaparsec per year. You can then ask what the rate should be if LIGO didn’t actually get lucky, but simply observed something that is happening all the time; the answer, remarkably, is between about 2 and 50 per cubic gigaparsec per year. The numbers kind of make sense!

The scenario would be quite remarkable and significant, if it turns out to be right. Good news: we’ve found that dark matter! Bad news: hopes would dim considerably for finding new particles at energies accessible to particle accelerators. The Core Theory would turn out to be even more triumphant than we had believed.

Happily, there are ways to test the idea. If events like the ones LIGO saw came from dark-matter black holes, there would be no reason for them to be closely associated with stars. They would be distributed through space like dark matter is rather than like ordinary matter is, and we wouldn’t expect to see many visible electromagnetic counterpart events (as we might if the black holes were surrounded by gas and dust).

We shall see. It’s a popular truism, especially among gravitational-wave enthusiasts, that every time we look at the universe in a new kind of way we end up seeing something we hadn’t anticipated. If the LIGO black holes are the dark matter of the universe, that would be an understatement indeed.