Many years ago I had the pleasure of attending a public lecture on cosmology by Martin Rees, one of the leading theoretical astrophysicists of our time and a wonderful speaker. For the most part his choice of material was unimpeachably conventional, but somewhere in the middle of explaining the evolution of the universe he suddenly started talking about the possibility of life on other planets. You could sense the few scientists in the room squirming uncomfortably — this wasn’t cosmology at all! But the actual public, to whom the talk was addressed, loved it. They didn’t care about fussy academic boundary enforcement; they thought these questions were interesting, and were curious about how it all fit together.

Since then, following Martin’s example, I have occasionally slipped into my own talks some discussion of how the particular bit of science I was discussing fit into a larger context. What are the implications of quantum mechanics for free will, or entropy for aging and death, or the multiverse for morality? To (what should be) nobody’s surprise, those are often what people want to follow up on in questions after the talk. Professional scientists will feel an urge to correct them, arguing that those aren’t the questions they should be asking about. But I think it’s okay. Science isn’t just about solving this or that puzzle; it’s about understanding how the world works. The whole world, from the vastness of the cosmos to the particularity of an individual human life. It’s worth thinking about how all the different ways we have to talk about the world manage to fit together.

That idea is one of the motivating considerations behind my new book, The Big Picture: On the Origins of Life, Meaning, and the Universe Itself, which is being released next week (Tuesday May 10 — I may be visiting your area). It’s a big book, covering a lot of things, so over the next few days I’m going to put up some posts containing small excerpts that give a flavor what what’s inside. You can get a general feeling from glancing at the table of contents. I also can’t resist pointing you to check out the amazing blurbs that so many generous people were thoughtful enough to contribute — Elizabeth Kolbert, Neil Shubin, Deborah Blum, Alan Lightman, Sabine Hossenfelder, Michael Gazzaniga, Carlo Rovelli, and Neil deGrasse Tyson.

This book is a culmination of things I’ve been thinking about for a long time. I’ve loved physics from a young age, but I’ve also been interested in all sorts of “big” questions, from philosophy to evolution and neuroscience. And what these separate fields have in common is that they all aim to capture certain aspects of the same underlying universe. Therefore, while they are indisputably separate fields of endeavor — you don’t need to understand particle physics to be a world-class biologist — they must nevertheless be compatible with each other — if your theory of biology relies on forces that are not part of the Standard Model, it’s probably a non-starter. That’s more of a constraint than you might imagine. For example, it implies that there is no such thing as life after death. Your memories and other pieces of mental information are encoded in the arrangement of atoms in your brain, and there’s no way for that information to escape your body when you die.

More generally, ontology matters. What we believe about the fundamental nature of reality affects how we look at the world and how we choose to live our lives. We should work to get it right.

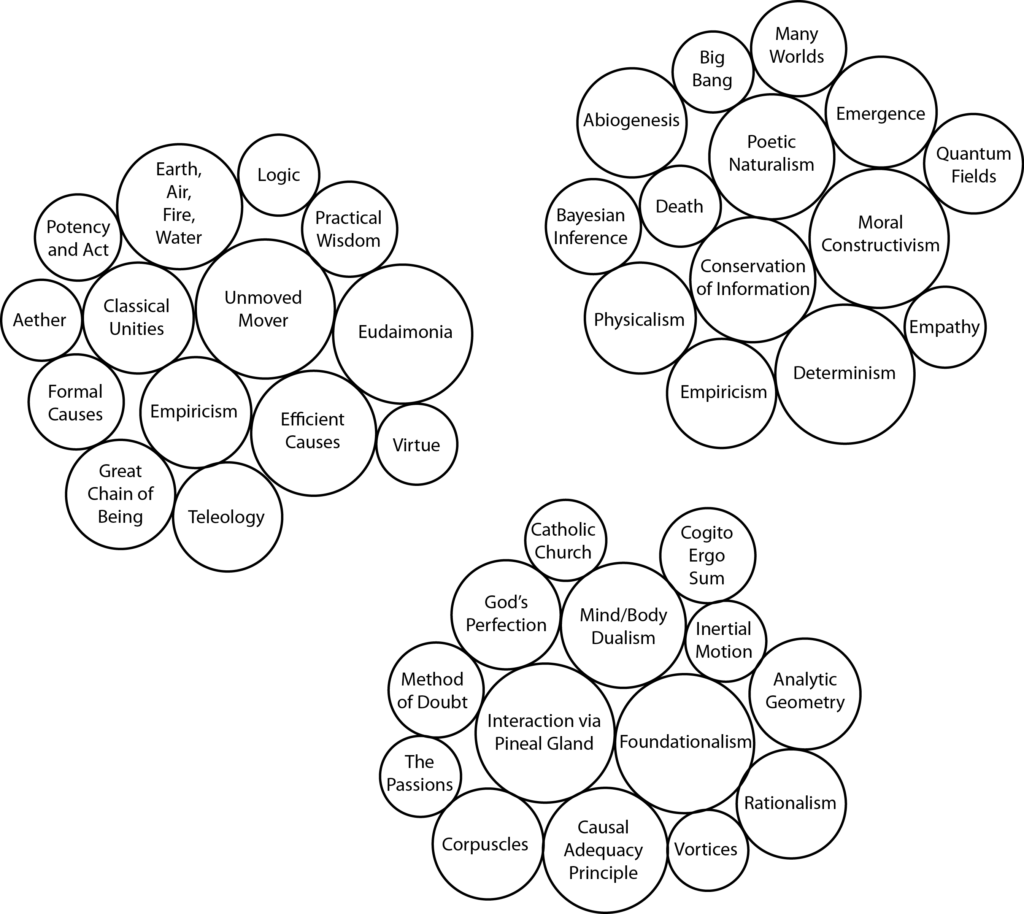

The viewpoint I advocate in TBP is poetic naturalism. “Naturalism” being the idea that there is only one world, the natural world, that follows the laws of nature and can be investigated using the methods of science. “Poetic” emphasizes the fact that there are many ways of talking about that world, and that different stories we tell can be simultaneously valid in their own domains of applicability. It is therefore distinguished from a hardcore, eliminativist naturalism that says the only things that really exist are the fundamental particles and forces, and also from various varieties of augmented naturalism that, unsatisfied with the physical world by itself, add extra categories such as mental properties or objective moral values into the mix.

Along the way, we meet a lot of fun ideas — conservation of momentum and information, emergent purpose and causality, Bayesian inference, skepticism, planets of belief, effective field theory, the Core Theory, the origin of the universe, the relationship between entropy and complexity, free energy and the purpose of life, metabolism-first and replication-first theories of abiogenesis, the fine-tuning argument, consciousness and philosophical zombies, panpsychism, Humean constructivism, and the basic finitude of our lives.

Not everyone agrees with my point of view on these matters, of course. (It’s possible that literally nobody agrees with me about every single stance I take.) That’s good! Bring it on, I say. Maybe I will learn something and change my mind. There are plenty of things I talk about in the book on which respectable good-faith disagreement is quite possible — finer points of epistemology and metaphysics, the connections between different manifestations of the arrow of time, how to confront radically skeptical scenarios, the robustness of the Core Theory, approaches to the mind-body problem, interpretations of quantum mechanics, the best way to think about complexity and evolution, the role of purposes and causes in our ontology, free will, moral realism vs, anti-realism, and so on.

The point of the book is not to stride confidently into multiple ongoing debates and proclaim that I have it All Figured Out. Quite the opposite: while the subtitle correctly implies that I talk about the origins of life, meaning, and the universe itself, the truth is that I don’t know how life began, what the meaning of it all is, or why the universe exists. What I try to advocate is a particular framework in which these kinds of questions can be addressed. Not everyone will agree even with that framework, but it is very explicitly just a starting point for thinking about some of these grand issues, not the final answers to them.

There will inevitably be complaints that I’m writing about things — biology, neuroscience, philosophy — on which I am not an academic expert. Very true! I’m pretty sure nobody in the world is an expert on absolutely everything I talk about here. But I’m just as sure that different kinds of experts need to occasionally wander outside of their intellectual comfort zones to discuss how all of these pieces fit together. My primary hope in TBP is not to put forward some dramatically original view of the universe, but to work toward a synthesis of a wide variety of ideas that have been developed by smart people of the course of centuries. It is at best a small step, but if it helps spark ongoing conversation, I’ll consider the book a great success.

So from people who don’t read the book very carefully, I’ll no doubt get it from both sides: “Knowing physics doesn’t make you an expert on the meaning of life, how dare he presume?” and “I read the whole book and he didn’t tell me what the meaning of life is, what a cheat!” So be it.

One thing that I meant to include in the Acknowledgements section of the book, but unfortunately it slipped my mind at the last minute: I should have mentioned how much my ideas about many of these topics have been shaped and sharpened by interacting with commenters on this very blog. Longtime readers will recognize many of the themes, even if the book presents them in a different way. I’ve definitely learned a lot from questions and arguments in the comment sections here (even if I’m usually too busy to participate very much myself). So — thank you, and I hope you enjoy the book!