Cosmologists have a standard set of puzzles they think about: the nature of dark matter and dark energy, whether there was a period of inflation, the evolution of structure, and so on. But there are also even deeper questions, having to do with why there is a universe at all, and why the early universe had low entropy, that most working cosmologists don't address. Today's guest, Anthony Aguirre, is an exception. We talk about these deep issues, and how tackling them might lead to a very different way of thinking about our universe. At the end there's an entertaining detour into AI and existential risk.

Support Mindscape on Patreon or Paypal.

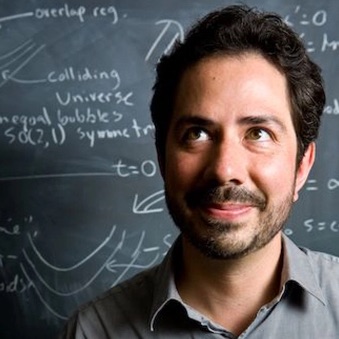

Anthony Aguirre received his Ph.D. in Astronomy from Harvard University. He is currently associate professor of physics at the University of California, Santa Cruz, where his research involves cosmology, inflation, and fundamental questions in physics. His new book, Cosmological Koans, is an exploration of the principles of contemporary cosmology illustrated with short stories in the style of Zen Buddhism. He is the co-founder of the Foundational Questions Institute, the Future of Life Institute, and the prediction platform Metaculus.

0:00:00 Sean Carroll: Hello, everyone, welcome to the Mindscape podcast, I'm your host, Sean Carroll, and today we have a cosmologist on the show, not just myself, another cosmologist, Anthony Aguirre, who I'm not going to be able to say this is giving you a typical view of what cosmologists think about, because Anthony and I actually are much more sympathetic with each other in our views of what are the important cosmological questions than we are with other cosmologists out there. But that's okay, it's my podcast. Anthony has recently written a wonderful book called Cosmological Koans, where he tries to introduce some of the mind-bending features of our cosmological universe through the device of telling little zen koans. If you're familiar with the idea of a koan, it's a little story that is supposed to bend your mind a little bit. Make you think about things that are apparently paradoxical.

0:00:52 SC: This is how the world works, the world itself is not paradoxical, but it can seem that way sometimes. So thinking about those paradoxes drives you to interesting places, and as a cosmologist, it drives you to think about things like entropy and information and what happened at the Big Bang, do we live in a simulation? Questions like this. So those are the kinds of issues that Anthony and I discuss in the podcast and we get to interesting places, because entropy and information are behind things like the existence of life in the universe, why you remember the past and don't remember the future. So, do we live in a simulation? These become interesting questions for human life as well as for studying the universe. And at the end, we mention the fact that Anthony has gone beyond studying the universe to actually found some organizations that worry about human life and where it's going.

0:01:43 SC: So it's a very fun conversation. We had to sort of bite our tongues because we wanted to rush forward 'cause we know our common background, but I think that we did a pretty good job of explaining things. Let me remind everyone that this is a podcast, you can review it on iTunes, which we always love, you can support it on Patreon, and you can go to the website to find all the show notes and transcripts and things like that: Preposterousuniverse.com/podcast. Thanks for all your support and let's go.

[music]

0:02:28 SC: Anthony Aguirre, welcome to the Mindscape podcast.

0:02:31 Anthony Aguirre: Thanks, it's great to be here.

0:02:32 SC: So you are a professional physicist/cosmologist but even with a little real astronomy in your background, theoretical astrophysics anyway, non-cosmological stuff, but you've written a book of koans. I'm not sure if I'm pronouncing that correctly, but the little zen stories. Could you explain to us why a purportedly respectable cosmologist would write a book of Zen koans?

0:02:55 AA: Purportedly respectable, yes. Well, it seemed like an interesting tool in the sense that what I really wanted to write a book about were those strange, fun, tantalizing paradoxes that you run into as a physicist or as a philosopher or just as a person who likes to think about things. I think there's sort of nothing more fun in my actual job as a working cosmologist or physicist than coming across something where you think, "Well, this is true and this is also plainly true yet those two things totally contradict each other or this is true yet it totally can't be true." And then you feel like you have sort of a puzzling mystery. And I wanted to get a sort of sense of that and that experience that I think we all have now and then of the weirdness and perplexity of the universe. And also in a way that attached the physics ideas and concepts and thinking to stories, because people are storytelling creatures.

0:04:04 AA: So the koan, I had some experience with reading books of koans before and had a sense of what they were about and a friend suggested it to me. A koan is sort of this device that's both kind of a story, kind of like a fable or a tale that encapsulate some idea in this case, but also kind of a confrontation. You should feel like I don't quite know what that's about or where am I with this after reading the koan, but then you go on and delve deeper into it.

0:04:36 SC: And so the point is that being a cosmologist is much like being one of these students being upbraided by the Zen master where the role of the Zen master is played by the universe in this case.

0:04:46 AA: Yes, that's the experience that I certainly have as a cosmologist and as a physicist, that you are constantly forced in this place of being bewildered or you're not doing your job right, I think. That's where the fun is.

0:05:01 SC: I sometimes try to make the point that people sometimes object to this or that cosmological theory, 'cause it doesn't feel right or it's disturbing or whatever. And I have to ask why that should be a criterion for anything at all.

0:05:13 AA: I think that's right, it's a tricky thing because on the one hand, physics, when you learn how the universe is it often violates your intuition that you had before, but then you, as a working scientist, generate a new set of intuitions that go along with the understanding that you've attained and that you really believe in. So it's always that tricky, is this violating my intuition because it's not right and I've built up an intuition that is a good guide to what's true and what's not. Or is it violating it, because I'm still stuck in some old erroneous intuition that I've just inherited from wherever? That's not always easy to tell.

0:05:54 SC: Yeah, because physicists definitely do, and in fact should use some kind of intuition, not all theories are created equal. We have a feeling that something is on the right track all the time and it is, as you said, very, very hard to convey that feeling or even to defend it in a court of law.

0:06:09 AA: That's right.

0:06:11 SC: So why don't you start us off by giving us an example, pick your favorite koan, or at least a good introductory koan from your book, which is called Cosmological Koans.

0:06:21 AA: Okay. Well, let's see, do you want me to just read one or just give you a sense of...

0:06:27 SC: Yeah, read one, do your dramatic interpretation.

0:06:29 AA: Dramatic interpretation. Okay. This one. Let's see. I'm trying to decide between the more Zen one or the more... Yeah, let's do this one. This one is called The Cosmic Now, and it goes like this. It takes place here and now. So I should say that most of these things are kind of part of a story that takes place in the early 17th century. So this one is an exception in that it takes place right here and now, wherever that is.

0:07:03 AA: And here it goes, it says, "Right now, as you read this, a baby in India is taking its first breath and an old woman, her last. A young woman and her lover sharing their first kiss. Lightning flashes across a dark sky. The wind blows through the hair of a solitary hiker in the Sahara desert. A satellite is seeing the sun rise above the Earth. A hurricane is blowing endlessly through the clouds of Jupiter. Two rocks are colliding, just now, in the third ring of Saturn. The New Year is arising on a planet around a star in our galaxy. Perhaps the world has inhabitants who are celebrating. Our galaxy moves about 100 miles closer to our neighbor Andromeda, toward their collision and union billions of years from now. A star in a distant galaxy ignites a titanic supernova explosion that ends its hundred-million-year lifetime. At the same time, hundreds of new stars first ignite. The observable universe adds enough space for a hundred new galaxies. All of this is happening, this very second, across the universe, right now. And yet this 'right now across the universe' does not exist."

0:08:08 SC: As a straightforward Western scientist I want you to say, "What do you mean it does not exist?"

0:08:12 AA: It does not exist. So the point of this one, is...

0:08:15 SC: I do you know what you mean, of course, but for...

0:08:16 AA: You know what I mean, of course. But the point of this... So we learned from Einstein's special relativity, that this idea that there is a single moment of now across the universe, a single meaningful time at which you say, "This was the past before this time and it is the future after this time," that that exists for an individual here and now observer, like you experience a past and a future and a now. But such a thing doesn't have an objective existence across the universe. That's what relativity tells us, is that if I attribute some moment of now spread out in space, someone else can attribute an equally valid one spread out in space that is different from the one that I have.

0:09:01 AA: And so there's a lot of reasoning behind that and where that truth arises from relativity. But I think the point here in telling it that way, was to try to really bring that into that relativity truth, which physicists pretty much all accept now and is sort of part of the standard canon of physics, into its violent clash with your intuition, because your intuition is just screaming at you, like even if something's far away, it either hasn't happened or it has happened, that there is a truth of the matter. And by putting yourself in that mind of envisioning all of these things happening at farther and farther distances, I think it sets up how very strange that really is. Even as a physicist, you get used to thinking, oh, there's no absolute now, and that's fine, and you know what the equations are in everything, but when you really think about it, that is really, really very strange.

0:10:00 SC: There's a little bit of a tension. I want to sort of restore your reputation as a respectable cosmologist by talking about cosmology, but I love this idea of using the koans because there's a bit of a tension between the presupposition of scientists that the world is ultimately logical and intelligible, and what I take to be the spirit of the koans, which is that sometimes maybe it's not, sometimes maybe you should give up on the hope of making sense of everything. Do you think that that's something to take into mind?

0:10:35 AA: Yeah, so I think it's interesting how different, some of these different questions and confrontations play out in different ways. So there certainly are a good number where there's something puzzling, like the fact that a wooden and an iron ball fall at the same rate, and yet there's an elegant, and in fact, beautiful explanation for why that is in physics. And once you understand that, you think, "Wow, that just really explained that nicely." And so there you really... It was puzzling, but then there's an explanation and you really have it, and you feel good about that. There are other ones where you feel like there probably is an explanation, but we don't know what it is yet, but we probably will get one and we'll feel good about it afterwards. You can... Things like quantum gravity, for example. It's very confusing how that is going to work. But I think we will have a theory of it at some point and we'll feel good about it.

0:11:36 AA: But I think there is a class of questions where it's not clear whether the question is flawed or whether it's an unknowable answer. When you ask things about probabilities in an infinite universe and things like that, that are... You just don't quite know if you're posing what feel like well-posed questions. But you're getting ambiguous answers, and it becomes rather unclear in your mind. Is this actually a well-posed question, or do I have to un-ask the question, as some Zen koans ask you to do. But if it's not that question, what is it... It becomes very unclear what is the right question to ask. So I think there are some where, I think, we don't know what the right question is, or whether the questions make sense, and then there are some where you feel like you're really asking a totally sensible question and just have no idea what the answer is or if we'll ever know. Like with the right view of interpreting quantum mechanics. It feels pretty solid, I feel like I understand what the issue is and just don't know. And Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, I believe one thing and the other days the other thing.

0:12:48 SC: Oh, don't worry, I have a book coming out about that that will fix all the problems and make everyone agree with the many worlds interpretation.

0:12:55 AA: No, I understand that. I'm savoring the mystery for the next few weeks until I...

0:12:58 SC: Savor the misery. You have a couple of months to savor the mystery. Good. But one of the wonderful things about the physics side of this, so I take your point that there are questions that we, by our intuitive lights or our folk way of looking at the world, make perfect sense to us, but maybe our experience with the universe teaches us that we should un-ask them. But the point is, we're forced into that, we try our best to understand the universe as it is, and we're driven to these crazy ideas about it, like there's no such thing as now. So why don't we ground ourselves a little bit in the universe. You mentioned relativity, Einstein's general relativity is the centerpiece of modern cosmology. Give us your short take on what are the observational established facts about the universe that we're going to have in the background as we start speculating a little bit.

0:13:50 AA: Well, I think in terms of... Well, there's gravity and there's cosmology, and of course those are intimately tied together in that Einstein's gravity gives us the mathematical framework to finally describe the universe as a whole. That was something that wasn't really possible to do very nicely before we had Einstein's theory. But now we do, and so we can understand that the universe that we see, that we can directly observe, is expanding and has been for the last 13.8 billion years, and is more or less uniform on large scales. And there's this set of astronomical and cosmological observations that have been fit together into this just remarkably, explanatory model, the standard cosmological model, that happened during our lifetimes. We were witnesses and in some small way a part of this. And it's really quite astonishing how successful that is, like the standard model of particle physics, that the real challenge is finding something that doesn't get explained reasonably well by it. There are...

0:15:00 SC: Yeah, it's tough times for theorists when your theory is doing too well.

0:15:02 AA: That's right, that's right. It's really fun for a while, and then you get really good answers to a lot of questions and pat yourself on the back. And suddenly you realize that you've made your job really hard, because once you have a really good theory... There are always lots of things sort of unexplained in detail, like how galaxies form in detail. And you can spend a lot of fun time and energy understanding that process better, but that's a different question from: Are there things that are sort of fundamentally at odds with or sort of have no viable explanation within cosmology? And we still have those things in the form of dark matter and dark energy, in the sense that we don't really know what those things are. But we do know their properties quite nicely. And once you suppose these few properties, you explain an awful lot.

0:15:58 AA: So I think it's interesting that for a book like this one, or just for a topic, that the whole universe, which is ultimately quite mysterious in a lot of ways, that we've nonetheless come so far in understanding in quantitative detail on the very largest scales we can observe and every timescale that we can observe, we have a pretty consistent picture of that.

0:16:22 SC: Okay, but share with our listeners what the actual statement of the standard cosmological model is, how Big Bang expanded the universe, dark matter, dark energy, that stuff?

0:16:30 AA: Yeah, so the universe started... Actually, I violated one of my rules by talking about the start of the universe when there's no need to.

0:16:39 SC: Yeah, I didn't want to say anything.

[chuckle]

0:16:40 AA: But the part of the universe that we observe, 13.8 billion years ago was an ultra hot plasma, nearly uniform, expanding filled with a tiny bit of normal matter, baryons, protons, neutrons and electrons, and some contribution of dark matter and some contribution, very small, of dark energy. And since then, that expanding gas has cooled and rarefied. It was nearly uniform, so the non-uniformities in that gas grew by self-gravity into large complicated structures, like now galaxies and clusters of galaxies, and within them, stars and planets and things.

0:17:29 AA: Meanwhile, the universe went through several transitions, where in the beginning it was more or less dominated by just radiation light. As time went on, that transitioned into being dominated by matter. And now we're in this period where the overall sort of expansion of the universe is dominated by this mysterious dark energy associated with empty space. And so we have this picture of a nearly uniform expanding universe that has evolved in time, that has kind of an early, middle and late phase to it. We're kind of in the middle phase. And a sort of explanation for where the structures that we see, from galaxies down to planets and even the origin of the elements that things are made of, we have a sort of origin story for all of those different things within this cosmology. Again, details not worked out, but broad brush kind of understanding in place.

0:18:29 SC: So, can I make a controversial claim right off the bat here?

0:18:32 AA: Yeah.

0:18:32 SC: I don't think dark energy's that mysterious. [chuckle] I think that we like to describe it that way, but if we think about dark matter, think about dark matter and dark energy and I want you to explain a little bit more of what those are and why we know that they're there. But there's a lot of different candidates for what the dark matter is. In an information theoretic point-of-view, the entropy of dark matter is high in the sense that we don't know what it is. Whereas we kind of know what the dark energy is, it's a cosmological constant. I would put greater than 90% odds on that. It's the energy inherent in empty space itself. So I think we should stop calling dark energy mysterious. It was surprising at the time in 1998 when we found it, but we probably know what it is unless there's some big surprise coming up in the future.

0:19:16 AA: I certainly agree that dark matter is sort of unexplained, but not at all particularly mysterious in that there are lots of candidates and as you say, why should everything the universe is made of happen to interact with light in ways that make it not dark matter. I'm, actually, I'm on record predicting that there will be multiple kinds of dark matter.

0:19:40 SC: Ooh, bold.

0:19:41 AA: That actually has started coming true, if you count neutrinos and we can imagine.

0:19:48 SC: Are you going to claim neutrinos as a victory for your prediction?

0:19:52 AA: No, no.

[laughter]

0:19:52 AA: I'll take it as a tiny little bit of data, but a real victory would be multiple sort of interestingly different ones. Anyway, I think it's, I agree that, I would put good odds against dark energy being anything other than a vacuum energy cosmological constant. The mystery I think, as you point out, is not that there is such a thing, but that the mystery is how to make sense of its value and what that tells us about the constitution of the universe as a whole, in that the natural value for the energy associated with empty space is absolutely not zero. There's no particular reason to think it's zero. There was a time when we could imagine that there would be such an argument, and people searched for that, but they never came up with a good one, and then we realized that that argument would be wrong, whatever it was.

0:20:47 SC: Yeah, it didn't work.

0:20:47 AA: Because it is not zero.

0:20:49 SC: I've the made arguments, I was very firm in my convictions. You could've won a lot of money off of me in the early 1990s, if you had bet me about whether there was a vacuum energy or not.

0:20:58 AA: From a lot of people, yeah, anyone... A lot of money could have been collected from lots of people, including me, I think. In fact, the first paper that I wrote was trying to disprove the cosmological constant observations.

0:21:13 SC: You're worse than me. Okay, good.

[laughter]

0:21:17 AA: So, I'm with you. But the natural value for it is some absurdly large number, like characteristic of the Planck scale, or the super symmetry scale or something like that, just absurdly larger than the value that we observe.

0:21:30 SC: Let's just be kind to our listeners and tell them what it is in this sense. What do you mean when you say cosmological constant?

0:21:37 AA: So it is the energy that you have when you say that there are no particles in some region of space. So what's important to keep in mind is that when you say a photon, a particle of light, what you really are talking about is an excitation of the electromagnetic field. And if you say there are no photons, that means there are no excitations, but the field is still there. And the same thing with any other particle, electrons or protons or quarks or whatever. Those things are excitations of fields that still remain in place. Just you say that they're in their unexcited or vacuum state if there are no particles around. But there's no particular reason to think that that unexcited state has zero energy with it, any more than if you have an ocean and there are some waves in it that are excitations on the surface of the ocean. You might have an unexcited region of the ocean but that doesn't mean there isn't something very important about the water there, it's just unexcited water.

0:22:34 AA: So once you take away the particles and the excitations there's still these fields around. And there's no particular reason to think that the energy per unit volume, the sort of density of energy in the fields, is zero. So if you take away the particles there still might just be energy, and that's what we call vacuum energy.

0:22:54 SC: And that's what we purportedly measured back in 1998, because it made the universe accelerate.

0:22:58 AA: Exactly.

0:23:00 SC: And so I think the last thing, we're going to start speculating about the edges of the observable universe pretty soon. So let's just remind the audience that we are in fact respectable empirically-based scientists and explain why we think there is dark matter, what the difference is between dark matter and dark energy. I think that there's still a lot of people out there, probably not Mindscape listeners, but you know out there in the world who think the dark matter is just cosmologists covering up for their mistakes, and there's probably something much simpler behind it all.

0:23:32 AA: Yeah, so there was a time when the reason to think that there was dark matter was because galaxies didn't have the dynamics you would expect, given the stars that you can see and the gas that you can see in the galaxy. So you would say, "Here's basically a spinning ball or disk of stars and gas. I can see how much stars and gas there are. I can use Newton's laws to tell me how their motion should be given Newtonian gravity, and that mass. And I see that their motions are not actually like that. The motion seems to indicate that there's more mass there than you can see in the stars and gas." And if that was the only thing that you saw, a reasonable thing would be to say, "Well, maybe there's something there that you don't see." Another reasonable thing would be to say, "Well, there might be something wrong with those laws of gravity in this new regime that you've explored." So, back in the early 20th century there was a discrepancy like this with the orbit of Mercury, people postulated that there were some extra dust clouds or something in the solar system that caused this perturbation in the orbit of Mercury that wasn't accounted for by Newtonian gravity.

0:24:49 AA: Turned out Newtonian gravity was wrong, and this was one of the pieces of evidence for Einstein's relativity. So it could be that such a thing was an indication that gravity is wrong. But this has become not a really viable explanation for dark matter anymore. So the time when it was just about galaxies is long gone. We have observations of galaxies, clusters of galaxies, gas clouds throughout the universe. The so-called microwave background radiation that tells us how gravity related to sort of variations in the density of radiation and matter in the very early universe. We've got all kinds of different gravitational lensing, there's all kinds of different pieces of evidence, all of which are explained by one assumption that there is this dark matter which is a gravitating but otherwise non-interacting component to the universe, with like five or six times as much density as normal matter, protons and neutrons and electrons.

0:25:56 AA: Once you make that assumption, all of these things are explained very, very elegantly, quantitatively. On the other hand, if you try to explain it away with modifying gravity, or come up with a viable theory of gravity that is different and explains all these things, I's extraordinary really difficult to do that, and I think there just isn't anything believable at this point that doesn't also even have dark matter in it.

0:26:20 SC: Yeah, as for the cosmic microwave background radiation in particular, I think it's essentially impossible to do it without invoking dark matter.

0:26:27 AA: Yes.

0:26:29 SC: So good. So we have a universe, we have a standard cosmological model, another one of these terribly dry and boring names for a magnificent edifice.

[laughter]

0:26:36 AA: Yes.

0:26:37 SC: And it does a pretty good job of explaining the universe for the last 13.8 billion years, from the beginning of the observable universe to today. So I want to talk about both the far, far past to the Big Bang, and maybe even before, but also the future. Let's go to the future first. What happens, is the universe going to re-collapse, is it going to expand forever? What are your feelings here?

0:26:57 AA: Yeah, this I think... There's kind of only one thing that this really depends on, which is whether the dark energy changes. So, if it really is a fixed cosmological constant, like you and I would both bet that it is, then the future looks pretty boring, at least in the local region, but boring on a very long timescale. I think it has to be kept in mind that although you'll hear that sort of... Although dark energy is taking over the dynamics of the universe as a whole now, and it's going to make astronomy and extra-galactic cosmology kind of boring within the next 10 billion years or so, we'll start to just see many, many fewer galaxies out there near us, nonetheless, that piece that is attached to us and will be in our absorbable universe for the long term because it's gravitationally bound to us, still has just trillions and trillions of years to go.

0:27:54 AA: So, I think there's a very big future. In some sense, we're sort of halfway through the age of the universe, in that the characteristic age of the universe is in the 10 billion year range, and so we're kind of middle-aged in that sense, but there's a really, really, really long retirement package that comes with the universe, of just many, many trillions of years, depending... And depending on what sorts of energy sources you think that we might exist around, whether it's long-lived, low mass stars or more exotic things like black holes, it could be just exponentially long times that we have ahead of us. So, it's a slightly strange thing that we're in... That the universe will go on for so long, I think.

0:28:43 SC: And so, explain a little bit about the dark energy not going away. I think that that's something kind of mysterious. Ordinary matter dilutes away, but dark matter doesn't.

0:28:54 AA: Dark energy doesn't.

0:28:55 SC: Dark energy doesn't, sorry. I'm going to get my... Going to be kicked out of the club. [chuckle]

0:29:01 AA: Yeah, that is in fact its characteristic attribute is that it doesn't go away when you make the space bigger because it's associated with empty space. If you make empty space twice as big, you just get twice as much of it, rather than it being sort of a enumerator, like you have an amount of stuff divided by an amount of space. Here, you have an amount of space divided by an amount of space and just nothing, nothing changes. So, it is... It's a strange substance and it allows... We'll talk about this, presumably, but one of the really neat things about dark energy is that it just seems to cheat a little bit in that it's... You take this amount of dark energy and you let it expand, which it wants to do, because the other property of the stuff is that it forces sort of an expansion of space-time, it causes a repulsive force that pushes space-time apart. So, it wants to expand, and in doing so, it makes more of itself. So, it's kind of this endlessly self-creating substance that I think has no real analog outside of... There are metaphors you can make, but I think there's nothing else really like it, at least in the physical world. Maybe there are things in economics that are somehow similar or something.

0:30:22 SC: But it doesn't violate conservation of energy? I'm sure this is what people are thinking right now.

0:30:27 AA: Yeah, and that is one of the most fascinating things, is how... And maybe we should get to talking a little bit about the early universe, because this is one of the coolest stories ever, I think, is how all of this stuff that we see can, in principle, without violating anything, come from almost nothing. So, there's a story, I think, that's just an amazingly fascinating one that we've built up, where you can start with just a tiny little bit of this vacuum energy, and that vacuum energy wants to make more of itself. So, it expands and creates a large volume with lots of energy associated with it, so it's created all this energy and you think, "Well, wait a minute. It's creating energy." But energy conservation is a tricky business, especially in general relativity. So, there are different stories I think you can tell as to how this makes sense. One story I think you can tell, which I think is not a bad story, is that...

0:31:21 SC: Let me just butt in to say that when we say stories you can tell, these are all stories that are translated from the original math, right?

0:31:32 AA: That's right.

0:31:32 SC: There is... The math is absolutely crystal clear, and the only question is what are the best words to attach to it to make ourselves feel better.

0:31:39 AA: Well, it's mostly crystal clear in this case, I think, as you'll agree. So, there's something that's totally clear, which is that energy can be positive or negative, and so, zero can be a sum of a big positive number and a big negative number. So, at least in principle, you can imagine, "I can take something with zero energy and turn it into some combination of positive and negative energy stuff." And that's a useful way, I think, of looking at this process where gravity provides negative energy. So, if you have a gravitational attraction between two objects, and put them on a scale, the two objects together will weigh just a little bit less, very, very, very little less, than the two objects weighed separately because the gravity between them actually has negative energy and that counts as mass, and so they have a little bit less mass when close together, and you can imagine the universe...

0:32:26 SC: Which you can tell, because it would take energy to pull them apart.

0:32:29 AA: It would take energy to pull them apart, yes. And you can get a little bit of energy out by letting them move together, so it's... And the universe plays this trick. So, in contemporary cosmological models, the universe just ruthlessly exploits this trick to create a just massive amount of positive stuff and negative gravitational energy that exactly compensates it, balancing the books nicely with zero energy to the entire universe. And this totally feels like cheating, but it's not.

0:33:01 SC: It does. [chuckle]

0:33:02 AA: It's totally allowed by mathematics. And I think when you have something that has such a surprising and sort of elegant explanatory power, but also is just totally what the math tells you is allowed, but completely violates your intuition, that I think is a fun thing. When you say we're so sure that nothing can come out of nothing, or that you can't have a whole bunch of stuff coming out of nothing, and yet physics just tells you exactly how you can do exactly that. That's a great thing to learn.

0:33:33 SC: Yeah. So, not only is it okay if the universe expands and there seems to be more and more vacuum energy, but the whole universe could potentially have exactly zero energy, and therefore be the kind of thing that could exist or not exist without violating conservation of energy.

0:33:49 AA: Right.

0:33:50 SC: Alright. So, tell... I do want to get there. It's up to you, I want to ask about the future because you painted this bleak picture and I want to know exactly how bleak it is. The stars... So not only are, the sun is going to burn out its nuclear fuel, that's a matter of a few billion years, but everything is going to go away, all the other galaxies are going to disappear.

0:34:13 AA: Everything that isn't bound to us at the moment is going to disappear, yeah. So the region of the universe that will be sort of connected together will be sort of limited. Now, I'm going to assume, as I think probably should be assumed, but we don't really know, that no faster than light travel or worm holes left over from the Big Bang, that we can sneak between or through are going to exist, so we really will be limited by the speed of light, so that means that our descendants or whatever is in our galaxy looking around billions of years from now will have just a smaller sort of set of stuff to play with than we do, in the sense that they won't be able to go to visit other galaxies and come back to report or even reach some of those other galaxies. On the other hand, if you were to imagine humanity cracking out into the galaxy and even going to neighboring galaxies and continuing to go to neighboring galaxies, there's a great deal of stuff that we could eventually inhabit. So I think starting now is essential in this program to...

0:35:27 SC: But if we're thinking big, everything in the galaxy is going to fall into a black hole and eventually evaporate away, long term, I should say.

0:35:35 AA: In the very long term, yeah, in the very long term. I gave a name to these sort of timescales in the book of kalpas, which is 10 to the like 3 digit number or 10 to the 10 to the multiple-digit number. So these are sort of timescales that are so long that they sort of make every other timescale that we care about ridiculously short in comparison to them. So yes, on those sorts of timescales there is a pretty bleak future. I guess I feel if the question is, "Is this a cause for sort of some sort of existential despair?" I don't know, really, I think what the universe will look like in our sort of conceptualization, what will be possible technologically a thousand or a million, let alone a trillion years from now. I think despite my faith that we really have understood lots of fundamental things about the universe, I want to have a little bit of humility and suggest that there may be lots more to it that even us great cosmologists still don't understand.

0:36:51 SC: Well, okay, that's interesting, because I want to be more hubristic, I guess, than you in the following sense, the universe is going to keep emptying out and, as you said, some things are going to be bound together. So, if it weren't for certain factors, you could imagine that the Earth would remain existent for infinity years, even though there's other galaxies far away that we would lose sight of. But I think that there are other factors. I think there's things like the second law of thermodynamics which I know you're also a big fan of, I think that life requires a source of low entropy in order to keep going, and that's sort of a buzz word-laden sentence and maybe you can unpack it, but I think that if you believe that then eventually we'll be done, there'll be no way for life to continue to exist forever.

0:37:39 AA: Yeah, so I think that's sort of the classical view of the so-called death of the universe that we reach this kind of maximum entropy state. And I think that that's probably true at some level, but I think there are a lot of subtleties to these questions once you delve into them. So I do wonder, and this is something that I think is worth talking about, whether... Well, yeah, maybe it's worth backing up a little bit and saying, talking about what the second law of thermodynamics means and is and what entropy is, because I think that the idea that entropy will sort of run its course and will come into equilibrium and then nothing interesting will happen again is probably true.

0:38:33 AA: But at the same time we also knew that somehow the universe started with this tremendously low entropy and tremendously large amount of information. We have no explanation for how that happened. And it could be that once we understand if there is an explanation for that, if we were to understand it, it might shed new light on that long-term question about the future as well, I simply don't know.

0:38:55 SC: What you mean by this is that there's no explanation that everyone accepts. There have been proposed explanations.

0:39:02 AA: I think there are, yes, there's no explanation I think that has the air of convincingness that, for example, the explanation for where all the stuff came from... So I think there's two sort of fundamental mysteries. If you talk about ultimate origins, where did all this stuff come from and where did all the information come from? Because a way to think about low entropy is lots of information. So the universe sort of started out with this huge endowment of matter and also this huge endowment of information and where both of those things are still around the information is a little bit different in that in some sense it, in some description, and we can get into this, it gets used up. The second law entropy increases and the information is kind of going away, whereas the matter kind of sticks around, although in less and less useful forms in some sense, but at any rate, the universe started out with this huge endowment of each which is the foundation of everything that exists in the universe now.

0:40:03 AA: The stuff forms the galaxies but the information allows the galaxies to form, it allows all kinds of entropy-increasing processes which are every interesting process to occur. Otherwise, we would just be in this very boring equilibrium state where nothing interesting happens. So there's a... In those twin mysteries of origins I think we have actually a pretty good explanation on the stuff side, the one that we discussed, that you can get it all out of nothing. And we have descriptions for where the different kinds of stuff came from, where the baryons came from, there are at least candidates for them, whether... But I think we have no such convincing explanation as to where all the information came from, other than sort of just assuming that it was there.

0:40:52 SC: I think we should dig into a little bit more what entropy is, what information is, and how they're related. Because I think that if you tell people that there was a lot of information in the early universe, they're going to think that there were a lot of hard drives and books and things like that. So, clearly, you mean something slightly different than that.

0:41:08 AA: Right, right. And it's not like that and it feels paradoxical also because the early universe was so boring and simple and yet we say that there was a lot of information to it. This is worth talking about it and what's difficult to talk about with entropy is that entropy is a very dangerous term in that people, even professionals, say it to each other, meaning quite different things and when they tell each other, "Oh, I mean this sort of entropy or that sort of entropy," then they understand each other, but nonetheless it's a complicated term.

0:41:41 AA: The way I think of it, I think of entropy as being two rather distinct concepts that people call entropy that can be connected. One concept of entropy might be called sort of randomness, that if you have a set of possible ways a system can be, you say it's got these different states that it can have, but you don't know which one it's in. So you have some ignorance for some reason about what state the system is in, you can assign probabilities to the different states the system is in. And entropy is kind of a measure of how uncertain you are about those states. So if the system is in exactly one state and you know that, then you would assign zero entropy to it, there's no randomness to it. You know what exactly what it is. If you assign equal probability to every one of the states, like you have no clue what state the system is in, then you would say that's maximum entropy and that's... You could say that that's equilibrium, though I think that's a slightly different way of thinking about it.

0:42:47 SC: So for the air in the room, for example, given that it's all spread out, I have no idea where any individual molecule is and that's high entropy. But if I knew it was all hiding in the corner, if all the air was in one corner I would know something about each individual molecule. I would have that information.

0:43:02 AA: Yes. But I'd like to... These concepts are related, but I think you're getting into the second definition of entropy that I'd like to come to after.

0:43:10 SC: Oops. [chuckle]

0:43:10 AA: I think, again, there are relations between them, but I think they're two conceptually somewhat distinct things. One is how much you don't know about the state of the room. And this is very directly connected to information, in the sense that when you learn something about a system, you have information about it. So if I say I don't know anything about the room or I don't know anything about the system, equal probability for anything, but then I go and make a measurement, and I say, "Ah, it's not in these states over here, it's in these, so let me assign zero probability to those states that I know it isn't and greater probability the ones that I know it is," then I've changed its entropy, the entropy is now lower for the system that I would assign to it, and I have information about it.

0:43:53 AA: A useful way to think about information is the difference between the entropy, or the randomness entropy that a system has and the maximum possible randomness information entropy that it would have. And you can show that this is exactly what we mean when we say you have 4 bytes of information or something like that. That you can correspond those exactly. So that's one information theoretic sense of entropy. And this is used all the time talking about communication and computer processing and all sorts of things where we talk about bits of information. It's exactly that concept.

0:44:28 AA: Now, there's another concept, which is the one that you just alluded to, which is to say... There's a whole bunch of states that a system might have, but I want to label them in different ways that are of interest to me. So I might, if I were in a kitchen, say, there are lots of different ways that my kitchen might be. But some of them are clean, and some of them are not quite so clean and some of them are pretty messy and some of them are super messy. And so I could give each state that the kitchen might possibly have one of those labels. And what I would find is that there are just, in general, if you're a normal person, very, very few clean states the kitchen can have relative to how many dirty states the kitchen can have. And this is a rather different thing, that we're choosing these labels, physicists would call them macro states, and assigning each state the kitchen can have, each detailed state the kitchen can have, to one of these macro states.

0:45:27 AA: Now, what you then find is sort of evidently if you then move the kitchen from one state to another, more or less at random, like you just go and putter around in the kitchen, or let your kid make a meal or something, they will randomly move the state of the kitchen from one state to another. And because there are lots more dirtyish states than cleanish states, it will tend to become dirtier and dirtier, that is the kitchen will just wander into a state of more dirtiness, because there are many, many more of them. So this sense of entropy, which you might call genericness, or disorder or something, really is a little bit distinct in that it has to do with the way that for some reason, we label these actual states of the kitchen into these macro states or these collections which have very, very different sizes. And those collections are sort of summaries for our use of, "Oh, it's useful for me to call all these states clean, and all these dirty for some reason."

0:46:35 AA: Now, what's interesting about these two notions of entropy is that one of them has a second law and is the thing that we talk about when we talk about the second law of thermodynamics, that's the second one. The first one... If I just say here are the states that the kitchen have, and I have probabilities of them, and I let the system evolve, then if the kitchen is a closed system, and if the laws of physics are what a physicist would call unitary, but we can call time reversible. Like if we could run the clock forward and backward in those laws.

0:47:11 SC: Deterministic, right?

0:47:12 AA: Deterministic, yeah. Then, that entropy will be conserved, that is there's no second law of entropy increase, there's just entropy is a fixed quantity.

0:47:21 SC: 'Cause the information you have about the system remains the same.

0:47:23 AA: The information remains the same, because it can't go away. If it did, you would never be able to get back that information by just evolving the laws of physics back. So these two notions of entropy, one of them tells you that information in your description of something is preserved if you keep track of it by carefully evolving the laws of physics. The other tells you that the information that you have about the sort of description that you have about a system, about its dynamics in terms of these different collections, this coarse-grained description that you have, that goes away in the sense that the entropy increases, the system gets more and more generic unavoidably and your handle on the system disappears. And that's the second law of thermodynamics in action.

0:48:10 AA: And it's inevitable in the sense that, it's inevitable to the degree that the variables that these... The smearing that you want to do as a big coarse-grained, macroscopic observer, is something that the fundamental laws that are evolving the state of the universe don't care about. Those laws are very simple. They don't know anything about clean and messy kitchens. And because they know nothing about each other, they inevitably have to drive you to these more and more generic states, and entropy increases. So I think it's important to distinguish those two, although there are relations that we could go into, but I'm not sure that it's worthwhile, and it's that second one that is the thing that is where the information is going away, where the entropy...

0:49:04 SC: Sorry, you have to remind us which the second one is. You have to remind us which is the first one and which is the second one. [chuckle]

0:49:06 AA: Well, yeah. So it's the genericness one, the disorder one that is increasing, even while in some sense, if there were a entropy of the universe in terms of the probabilities of its states, that would just be sitting there. Information will be preserved.

0:49:23 SC: So there's a sense in which the early universe was very orderly and that's what we mean when we say that it was low entropy. So what is the relationship there then with information? Because you said that there was this large amount of information we had.

0:49:34 AA: Right, so again, I think... If you think of the orderliness, you can also think of it a gap between how disorderly something could be and how disorderly it is right now and call that order or specificity or something. And that is the thing that is going away as the universe ages or as any physical system ages, is entropy increases and so the universe was endowed with a tremendous amount of that, whatever that you want to call that order, at the beginning. And we know that because we've watched that order decay away as the second law has unfolded through the history of the universe. There are lots of processes that we can see that are using up that order and...

0:50:21 SC: Stars shine, black holes form, we breathe, yeah.

0:50:25 AA: Things clump together, the grass grows, people metabolize stuff. So there's this chain you can see from that early order to clumping stars, starlight, plants, people eating it and metabolizing it and ultimately we're using that primordial store of order every time we eat something, and that eating allows us to stay out of going to equilibrium as a nice closed physical system. Our tendency if just left to our own devices would be to go to higher entropy. That is very bad for a living system to go to a dramatically higher entropy than it is. So we have to maintain the entropy that we have. And we do that by ingesting stuff that has information content to it and giving off waste that has much less information or much more entropy off into our environment. And so we stay... We're not a closed system, we're a kind of an open system, but we stay in sort of an enduring macroscopic configuration that we call a living thing, despite the laws of physics wanting us to go to higher entropy.

0:51:42 SC: I think there's something confusing to me, 'cause I do think I understand this stuff, but you're very properly drawing a distinction between the information way of thinking about entropy and the disorderliness way of thinking about entropy. But then you say the universe is low entropy at early times in the messiness sense. And that's useful for life existing but then you switch to saying, well, we ingest high information food.

0:52:10 AA: I probably should have said high order foods in that case.

0:52:12 SC: Okay, good. Then suddenly everything makes sense again. Good. So yeah, so this is worth emphasizing that life itself is a process that both relies on and assists with the tendency of the universe to increase in its disorderliness.

0:52:34 AA: Yes, so I think it's both. So if you had no entropy increase, I think you wouldn't have living systems, in the sense that the things that we actually do, the metabolism that we do, are all entropy-increasing processes. But I also think it's fair to say that a lot of what metabolism is doing is maintaining homeostasis in the face of this tendency to go to disorder. And the only way to do that is to embed ourselves in a larger orderly system and consume some of that order, in order to maintain that homeostasis.

0:53:10 SC: Does this run the...

0:53:10 AA: And that larger orderly system is the sunlight and the biosphere and the universe beyond that that has much more order, has a big reservoir of order to it that we are allowed to make use of.

0:53:23 SC: Would you say that this suggests a kind of entropic explanation for why the early universe had low entropy? Because without that low entropy we wouldn't be here talking about it.

0:53:32 AA: That's certainly true. Whether that's an explanation or not I think is a longer discussion.

[chuckle]

0:53:38 AA: But yes. It's certainly true that it's I think...

0:53:39 SC: If you were to give a yes or no answer?

0:53:41 AA: I think it's probably true that if you just had an equilibrium universe in the most generic state that you wouldn't have... There's a lot of words to hedge here, for reasons that I think you well understand, that you certainly wouldn't have a world like we experience it, I would say. And I think that's mostly true. At the same time there's a lot of tricky business to entropy, in the following sense. So, and this has to do with what we might call indexical information.

0:54:27 SC: What's that?

0:54:29 AA: So that is... So suppose you have a bunch of ants in a big ant farm or something. Now, you could describe properties of these ants, like they tend to have this sort of speed walking around, they tend to have this much food in their stomachs, or whatever, statistical properties of the ants. And you could then attribute an entropy that was connected to those statistical properties, and you could say that, here's how much information we have about this big collection of ants, right? And that would be some amount of information. But now, suppose you pick out a particular ant, so now you don't have a bunch of vague statistical distributions, you have particular properties of that ant. So that, there's a lot more information associated with that particular ant, than there is with a whole group of ants. Because the whole group of ants has statistics which are more vague, an individual ant has a very precise number, so it's a lot of information.

0:55:28 SC: A lot more uncertainty with the group, yeah.

0:55:31 AA: Now, what's the weird thing is you take a bunch of ants, each of which has lots of information associated with it, you put them all together and you get something without much information associated with it. So this is a strange thing about information, it's not quite additive in that sense. You take a whole bunch of individual high information things and put them together, and you get something that is lower information. And similarly, you can imagine...

0:55:58 SC: I mean, because you forgot something right? Because you...

0:56:01 AA: Because you for... Yes, yes, because you didn't keep track of...

0:56:05 SC: Which ant is which.

0:56:07 AA: If your collection of ants was your full description of each individual ant, then you'd still have all that information, but once you start to treat it as a collection, you lose that.

0:56:16 SC: Yeah.

0:56:16 AA: So now, the information that we have... So, as we... As I individually look out into the universe, there's a particular point of view that I have, and associated with that are a bunch of very particular things about the universe. There's a particular room that I'm in, the particular planet that I'm on, in a particular galaxy, and so on. So that's a whole bunch of information that is associated with me, right? If I take the description of the universe as a whole, it's not clear that that information is still there. What the universe as a whole might have are things like, how many planets there tend to be around a star, and how many stars there are in a typical galaxy, and things like that. So you can imagine that the universe as a whole might actually have very little information content, because all it really has are statistics. Whereas when I take a particular view of the universe, my view, there's a ton of information associated with that.

0:57:11 SC: Sure.

0:57:11 AA: And that is both sort of clear and also weirdly paradoxical, because it also has that feeling of creating a whole bunch of information from nowhere, right? Where did it come from? It just came from being me.

[chuckle]

0:57:24 AA: And that's very easy to do.

0:57:27 SC: Yeah.

0:57:28 AA: Like, almost no effort. When I think about the ultimate origin of the sort of information in the universe, and is there a cheat similar to the cheat that we got in creating the origin of the matter, that's sort of where I look, like, is there a way in which we can get a whole lot of information for free, even though from another standpoint, it seems like there really isn't much information. And so, I think at some level, that's true, but I don't think that that's an explanation at the moment for where the information in the universe comes from. But if there were an explanation, I think that might be some aspect of it.

0:58:10 SC: I mean, my answer would have been that the entropy of the early universe was way lower than it ever needed to be for any simple entropic argument, but... So this comes into the idea that if you were an equilibrium, if the universe was just the cosmological equivalent of a big box of gas at high entropy, there could be fluctuations, right? I've heard people talk about this idea of fluctuating into a lonely brain floating in the cosmos, the Boltzmann brain.

0:58:38 AA: I thought we agreed we weren't going to talk about that, Sean.

0:58:39 SC: No, you agreed on it.

0:58:40 AA: Okay. [chuckle] That's great.

0:58:40 SC: That is not really... You can't really agree. We did not share our mutual information.

0:58:43 AA: I thought I agreed that I would not.

[chuckle]

0:58:45 SC: No, you actually, to be very, very technical, you said you were happy to talk about it, it's just annoying. So I took as that as assent.

0:58:51 AA: Okay, I stand by that.

0:58:52 SC: But we're providing a service here at Mindscape. We know that people out there in the audience have heard of Boltzmann brains. If you think it's annoying and shouldn't be a big part of science, then please tell us why, but first please tell us what the idea is.

0:59:04 AA: No, it's annoying, it's annoying on multiple levels, and part of annoying is of course interesting. I should specify when I say something is annoying that a lot of the projects that I've worked on and found most fruitful in my career have been born of being very annoyed at something. So this is not necessarily a negative thing, ultimately. And Boltzmann brains are one of those things that I think almost anyone who thinks about them would agree that they're annoying, yet also provocative and interesting. And so the notion here is that, if you imagine a system that is in equilibrium, the statement was that system is boring, it's kind of information-free, it just sits there. All of its properties follow from the fact that it's just an equilibrium. And yet, we also know if we think about the kitchen, that the kitchen will just stay messy essentially forever, but if you let your kid mess around in the kitchen long enough they might accidentally clean something up.

[chuckle]

1:00:10 AA: And it might go down in entropy a little bit. And so any equilibrium system is like this, it will from time to time sort of accidentally wander into a lower entropy, more ordered state. And so you can imagine saying, "Well, yes, we live in an orderly universe, but maybe it just wandered into that orderly state."

1:00:32 AA: There's really no mystery there. We just... The universe is in equilibrium, but it occasionally wanders into an orderly state and we find ourself in one of those orderly states. And so, the Boltzmann brain argument is pointing out the flaw in this reasoning, which is essentially, that the universe that we actually see and infer is out there, using science and other means, is way, way, way, way, way, lower in entropy, that is a much, much bigger fluctuation if it were one, than is necessary to account for our just first person experience of existing as a thinking being. All that it would take to exist as a thinking being is a single brain or some simple system... Not simple, some incredibly complex, but small on a cosmic scale system, like a brain, it could think, "Oh, here I am," for a moment. And in fact, it could account for any set of first person perceptions that you might imagine, you can imagine a physical system that would have that set of perceptions and whatever that is.

1:01:42 SC: Like I see a galaxy, I see the cosmic microwave background. All of that could...

[background conversation]

1:01:47 AA: Whatever you postulate, this is the data that I want to explain. You can imagine a very, very small system like a brain that would observe that data, but then nothing more interesting. After a very short time, that system's experience would very radically diverge from the experience that we have in the world as being... As having originated in a sensible cosmology like we do. Now, people's viewpoints of this vary a little bit. Some people would say the assumption that we're a Boltzmann brain kind of makes a prediction which is immediately falsified by the fact that the universe goes on and doesn't disassemble into chaos or something. That's one point of view. You can also say something like, "If we're really a Boltzmann brain, then we don't know anything. And we can't trust our reasoning, we can't trust our perceptions, we can't trust anything." That's just a self-undermining way of thinking, like it's not a consistent thing to think, because there's no reason to even trust that my memory of two seconds ago when I was talking has any reality to it. I think that... But what people agree on, I think, is that entropy fluctuation downward simply is not a viable explanation for how we found ourself in the low entropy state we find ourselves in. At least not in and of itself.

1:03:18 SC: Sorry, sorry. Yeah, so sorry. Not just that we're not individually Boltzmann brains or something like that, but we don't live in a Boltzmann universe.

1:03:25 AA: Right, right, so the Boltzmann brain is really just a kind of reductio ad absurdum for thinking that the universe as a whole fluctuated down into a low entropy state. And I think it actually is probably... Would be a lot less confusing not to talk about brains, but just to talk about the universe. And then there'd probably be a lot less arguments but...

[chuckle]

1:03:49 SC: Probably.

1:03:50 AA: It's a fun thing to think about.

1:03:51 SC: Yeah, but so where does it leave us? We agree that life, what you and I think of as life, a certain process going on in a complex system here on Earth, maybe elsewhere, relies on the fact that we live in this very low entropy universe, where entropy is increasing a little bit. That's where we get food from and that's how we make interesting things. It may or may not go on forever, I would say it can't go on forever. I think you eventually reach high entropy. You want to be more cautious about that, I can't really argue with that. We don't know why it started low, in the very, very early universe. These are facts or at least are very solid arguments. What do they teach us about cosmology, what are the lessons that we can draw for how we should be thinking about the universe and what the job of professional cosmologists should be?

1:04:41 AA: Well, that's an interesting question. One step, I think, is to ask, even if we don't get a full answer to where did the information come from or why did we start in low entropy, we might get a partial answer, in the same way that we got at least a partial answer to where did all this stuff come from. We didn't talk much about inflation, although we talked about it without naming it inflation. Inflation is a vacuum energy dominated early phase of the universe, that would be the name for the process where all of the stuff came from by reproducing lots of space full of energy. Inflation also does things on the entropy front which are a little bit more controversial. But what I think it uncontroversially does is create a lot of region of space which looks like low entropy, as long as you don't worry about the space-time degrees of freedom.

1:05:48 AA: If you just think about the matter that is in space-time, what inflation does is make a nice big uniform chemically simple state of matter that is very, very low entropy, and that is the state from which you can generate lots of order that comes later in the form of stars and interesting chemistry, and all of that stuff. I think there's a sense in which inflation is a crucial ingredient in understanding how information and order and its generation and usage actually happened... Could have happened in the universe, without necessarily being an ultimate answer to the question of where did all the order come from. I think that's a much trickier thing to assess with inflation.

1:06:43 SC: As a good Bayesian, what is your percentage chance that... What is your prior that inflation actually happened in our universe?

1:06:50 AA: 82%.

1:06:51 SC: Alright. I'm down to like 50-something percent. I'm more skeptical than you are. I think that you alluded to this very quickly but maybe for the listeners out there, we should emphasize inflation does seem to create the kind of universe that we live in, but only at the cost of assuming a very, very low entropy condition to begin inflation in the first place. So you've pushed the mystery back more than solving it.

1:07:12 AA: You've pushed the mystery back, though I would claim that we don't really know how to specify what the entropy of the space-time... When you say inflation had to be a very, very low entropy state, I think we don't quite know how to actually rigorously define that entropy that would be low.

1:07:32 SC: Well, if you think that it was low entropy at the end of inflation and you didn't think that entropy magically went down, you must think that it was even lower before inflation.

1:07:38 AA: Right. So we're assuming that there is a thing called entropy and that it still has a second law...

1:07:43 SC: Yeah, that's right.

1:07:44 AA: And therefore, it inevitably had to be lower earlier, that's all you can ever get. But if that's the assumption, you sort of... You're never going to get out of the mystery so...

1:07:55 SC: Oh, I think you can.

1:07:57 AA: Well, yeah. So if you... Yes, if you assume that the information, the universe is simply endowed with an infinite amount of order, then it's true that no matter how much you use up, there's still an infinite amount left. So whether that is a satisfactory explanation is probably a longer conversation for another time. That would be great fun to have.

1:08:18 SC: But we do both agree that this is a big puzzle for cosmology, and I think that to help our non-experts out there, we're in the minority in some sense. This is not one of the questions that most working cosmologists would bring up as one of the big puzzles they're trying to look at.

1:08:34 AA: It's true, but I think it's vastly underappreciated in that sense because it really is the ultimate question of where everything comes from in a way, because everything in a large sense, I think, is made up of this order. All of the things that we describe, all the stars and planets and things, the thing that makes them all possible is this reservoir of order that we inherit from the early universe. Otherwise, everything would just be super boring. And so, this growth of entropy or this growth of order throughout cosmic history is driving every interesting process that everybody cares about.

1:09:14 SC: It's quite a big deal.

1:09:15 AA: So in that sense, it's a vastly underappreciated and super important topic, as I'm sure you would agree, having spent lots of time thinking about it. But it's true that it's brushed under the rug in comparison to, I would say, much more prosaic concerns in some sense that are still interesting but aren't... Yeah, I agree that it's just we're a minority, but we shouldn't be. Everybody should be worrying about this.

1:09:39 SC: No, we're totally right, that we can agree on too. We haven't used the phrase yet but we've been talking about the increase of entropy and disorderliness and what we usually say is that defines the arrow of time, or at least the thermodynamic arrow of time, the difference between past and future. And as you just said, I think maybe it's worth sort of elaborating on this idea. This fact that entropy is increasing really underlies all of the interestingness of our lives. It's hard to overemphasize how important this is. So things like memory, cause and effect, free will. They're all ultimately traceable in some sense to the fact that entropy is increasing all around us.

1:10:19 AA: I can only agree, yes.

1:10:21 SC: Well, you can do more. You could...

1:10:22 AA: Well, I can do more. I can say more about that?

1:10:23 SC: Well, in the following sense. I do this myself. I say those statements because I believe that they're true, but I think that just as cosmologists haven't focused on why the early universe had a low entropy enough, the rest of the world hasn't focused enough quite on elaborating how that increase of entropy over time gives rise to all of these different phenomena.

1:10:48 AA: Yeah, I agree, and I think everything... In some sense, everything that happens has this character to it in that happening is sort of a change in something, like something, there was one state and then there was a different one. And when everything... If you imagine everything being either in equilibrium or in a description where the entropy was not changing, then there's a sense in which nothing is really happening in that you can just run the clock forward and backward and you can't really distinguish the later thing from the earlier one, like everything that's in the later one is in the earlier one and vice versa. The fact that there's something new or that there's something lost, there you're talking about not the fundamental dynamics of the system, not the sort of unitary dynamics, but you're talking in terms of a different level of description of the system that's happening in these coarse-grained or macroscopic or something variables, which is that arena in which the second law is operating and in which you can talk about information changing or going away, or being generated in some sense.

1:12:10 AA: And I think that's the worlds or that's actually many worlds, like many different levels of description, which are the world that we actually inhabit. So anything that we talk about as where we're using a level of description that isn't like the wave function of the universe is evolving according to Schrödinger's equation, any other way that we describe things, we're talking about it in this more coarse-grained way in which the tendency of that sort of the relationship between that description of the world and the fundamental... The wave function description of the world is absolutely... Is sort of central and that is the second law of thermodynamics, that like the tension between those two descriptions that is driving entropy increase is sort of responsible for everything. It's responsible for that there is a future and a past that are different, that you can't go back in time and just tell what happened in the past, that you predict the future and you remember the past, that there are records. All of these things that just are our everyday, moment-to-moment existence just are inexorably associated with that second law.

1:13:22 AA: And I think you're right that... I too say those words while appreciating that actually, if pressed on how exactly is it that we get records of the past and only prediction for the future. It's very, very hard to pin down in concrete terms, or how is it that we can cause the future and remember the past and not vice versa? Actually formally carefully specifying those things is enormously subtle to do. And I think that project is... People think about that, but is largely undone in my book.

1:14:04 SC: Well, your organization gave me a grant to think about it, so I do have a paper coming out that I think you'll be very interested in.

1:14:09 AA: Well done, well done.

1:14:10 SC: Speaking of which, we have this situation that you described very eloquently where the universe makes sense in the sense that there are laws, there are rules, it's not just crazy chaos breaking out all the time, but there are these looming questions like, why does universe exist at all? Why does it have a specifically low entropy in the beginning? Do these features of the universe as we see it lend credence to the idea that maybe we all just live in a computer simulation, not in a naturally forming universe?

1:14:42 AA: I'm not sure why they... Which features would lend credence to us being in a simulation?

1:14:47 SC: Well, we need to attribute some psychology to our simulators and maybe they're just starting from some simple initial conditions, and seeing what happens, and we end up as part of the backwash.

1:15:04 AA: Yeah, I guess I don't see it as a sort of evidence either way, I think...

1:15:13 SC: But what do you think of the argument in general? Let me not be so specifically provocative in that direction.

1:15:18 AA: Well, there are a bunch of different things that you might call a simulation argument, some of which I think are total nonsense and some of which are both... Are only somewhat nonsense, but also very hard to rule out. So there's one species of thing that says, given enough technology in 100 or 200 or something years, we will be able to run simulations of say what happened in the second half of the 20th century on Earth and historians will be delighted with this because then they can go back and think about what would have happened if the Nazis had won the war, and all kinds of interesting counterfactuals and things like that. And so these simulations will be so detailed that they'll have to simulate down to the neuron level of the beings in them to get the simulations right. And so if we assume that the beings in those simulations are self-aware, just like we are, then you end up in this situation where there are all these simulations being done of all these beings, and so why aren't we one of those beings in one of those simulations that will be run in our future?

1:16:31 AA: Okay. So this is something that is called the simulation argument and was formulated in this kind of way by Nick Bostrom. I'm profoundly, profoundly skeptical of this argument in that I think it will turn out that in order to simulate even a bacterium in a useful sense will turn out to be impossible given the computational resources of the universe. And that the only way to really simulate a bacterium will be to create a physical system that is like isomorphic to a bacterium.

1:17:09 SC: Make a bacterium.

1:17:10 AA: Create a bacterium, basically. So this will just not be an exciting thing to do. Like yes, if you're a super civilization, you can make lots of versions of Earth and see how things played out, but you don't get anything for free. You'll be creating lots of Earths and okay. So I guess, I find that version of the argument not compelling. On the other hand, you can sort of ask if the universe, if you ask what is the universe really made of and your answer is first like, well, it's made of atoms which are made of subatomic particles. Fine, but if you ask what are those particles, then things start to get a little bit more slippery. They're excitations of a quantum field or they're sort of things that are pointed to by a wave function. What is a quantum field made of? Well, a quantum field is like made of the ability to create particles. It gets very circular. And if you ask, what is a wave function? It's a description of where particles will be when you measure them, neither of these have a sort of tangibility to them, and they have more like a feeling of an information theoretic thing.

1:18:27 AA: And this leads you, if you think about this a long time, you sort of feel like, well, ultimately, the universe maybe is a sort of informational entity and then you start to think, well, what does that mean? Who's got the information? What is it like... The floor drops out from under you a little bit when you start to think along those lines. And then if you think the universe is sort of this information thing, could it be that that information is in some larger set, it's a simulation in some super duper computer, who knows? I think it's rank speculation after that point, but I think the thing that gets you there to think, what is the fundamental constitution of reality? I think we've actually shed a lot of interesting light on that, and it's just much, much weirder and kind of disquieting than you could imagine, when you're so used to thinking of the universe as made of little bits of stuff.

1:19:27 SC: Yeah. Well, this goes back where we started it and the fact that if you do science well, it should be a little discomforting at the end of the day.

1:19:35 AA: Indeed.

1:19:36 SC: We've been very... You talked about the big picture of the whole universe, and where it comes from, what that implies and how life can exist in it, but you've also been more practical in your concerns about the universe. You seem to, every couple of years, start a new organization of some sort. Why don't you share with the listeners like some of the various organizations that you've had your fingers in the pies of?